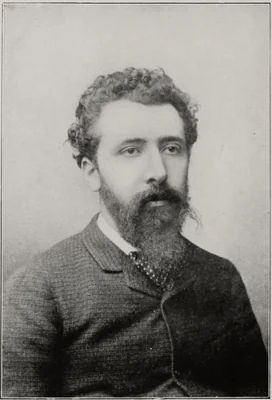

Georges Seurat

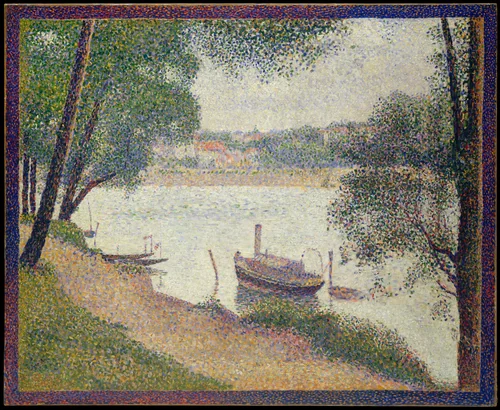

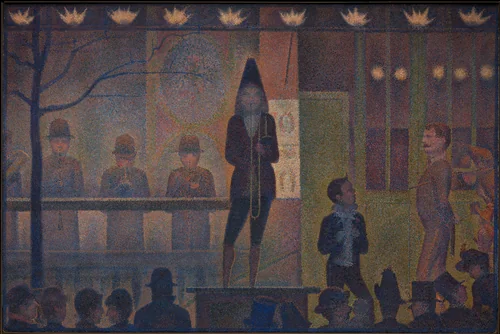

Georges Seurat (1859-1891) stands as a pivotal figure in the transition from Impressionism to the calculated, structural language of modern art. Although his career was tragically brief, his methodological rigor established him as the founder of Post-Impressionism’s scientific wing. He was not merely refining existing modes; Seurat fundamentally devised the systematic painting techniques known as chromoluminarism and its more recognized moniker, pointillism.

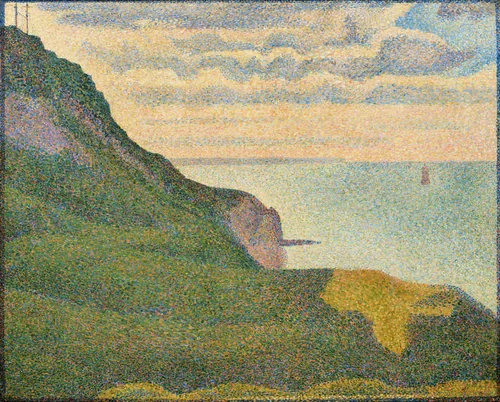

Seurat approached the canvas as a problem to be solved through optics and color theory. Where the Impressionists sought spontaneity and the fleeting moment, Seurat enforced rigorous control, applying tiny, individual strokes of pure color that were intended to blend optically in the viewer’s eye, rather than on the palette. This commitment to empirical structure over momentary sensation distinguishes his output. His method demanded exacting preparation, turning the act of creating Georges Seurat paintings into a precise, almost engineering exercise in visual science.

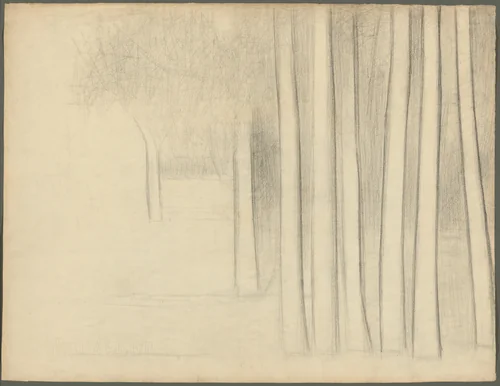

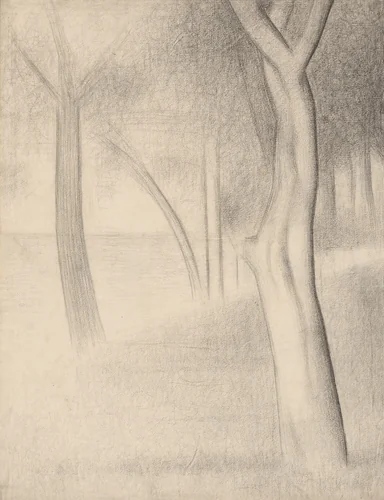

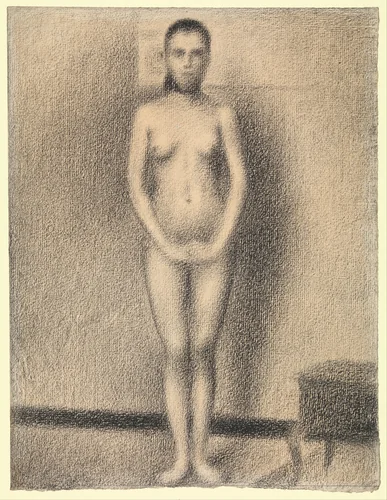

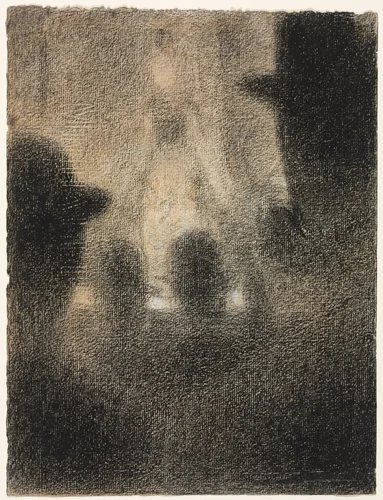

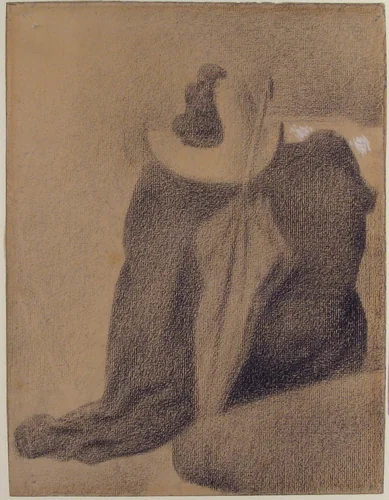

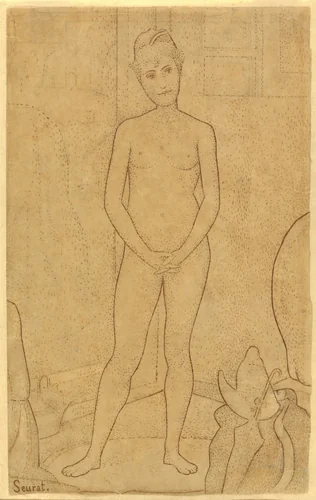

The foundation of Seurat’s unique visual sensibility lies in his prolific drawing practice. While he left behind only four completed paintings, the surviving eleven drawings reveal a mastery of light and shadow achieved through specialized materials. He utilized conté crayon extensively, applying it to paper with a distinctly rough surface texture. This combination allowed him to create dense, velvety fields of black and white, transforming mundane subjects, such as A Man Leaning on a Parapet and the starkly observed Landscape, into profound studies of atmospheric depth. Early works, like the detailed Architectural Motif: Double Acanthus Fleuron, demonstrate his commitment to classical structure, a curious counterpoint to his revolutionary optical experiments.

Despite his early death at the age of 31, Seurat’s impact was profound, directly influencing subsequent generations of artists seeking objective means of expression. Today, many of his works, including preparatory studies like The Hand of Poussin, after Ingres, are housed in premier collections such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Art Institute of Chicago. The detailed preparation inherent in his method ensures that his work, whether in original form or as high-quality prints, retains its powerful visual vibration. Consequently, many lesser-known studies and drawings are now considered royalty-free and available as downloadable artwork for scholars and enthusiasts worldwide.

Source: Wikipedia · CC BY-SA 4.0