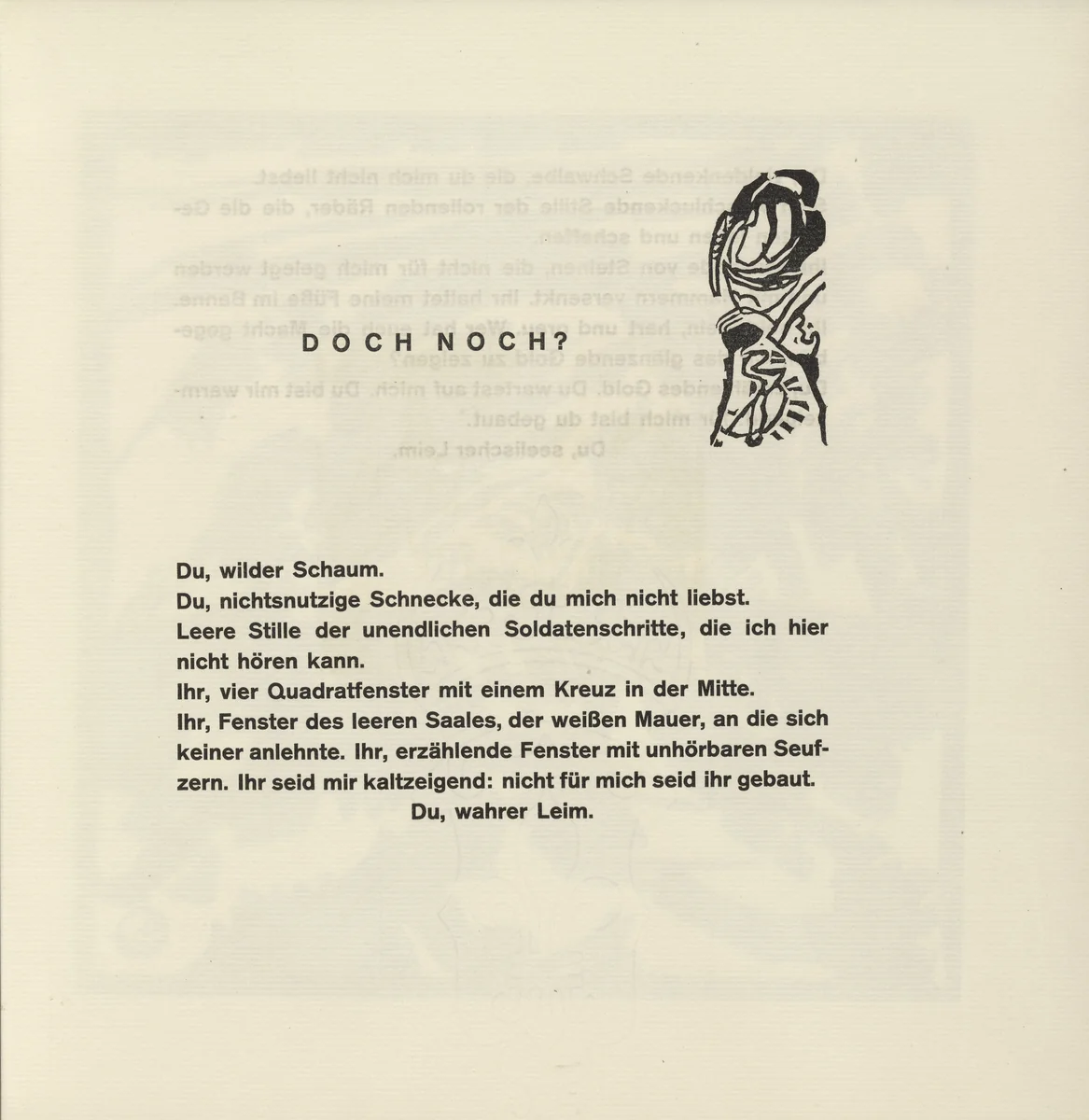

Vignette next to "Still"? (Vignette bei "Doch noch?") (headpiece, folio 27) from Klänge (Sounds) by Vasily Kandinsky is a pivotal example of graphic abstraction created in 1913. The work is a woodcut, one of fifty-six such prints compiled into the artist's highly influential illustrated book, Klänge (Sounds). Published in Munich, this volume paired Kandinsky's radical abstract imagery with his own free-verse poetry, attempting a comprehensive synthesis of visual and auditory experience.

As a headpiece designed for folio 27, this woodcut functions as a visual prelude or counterpoint to the accompanying text. Kandinsky utilizes the inherently sharp contrast of the medium to maximum effect, employing bold, interlocking black forms that convey intense movement and structural instability. Unlike earlier graphic works, the forms here are almost entirely non-representational, focusing instead on establishing dynamic rhythm and psychic resonance. This composition embodies the artist's theory that abstract forms possess inherent "inner sounds" capable of affecting the viewer directly, echoing the musical term Klang (sound or tone) used for the book’s title.

Created in 1913, the work sits at a critical juncture in the history of Modernism, marking the full maturation of abstract expression. Although Kandinsky was Russian and based in Germany during this period, the cultural classification of French reflects the widespread global exhibition and critical reception of his pioneering theories and illustrated book projects across Europe, solidifying his international renown. The technique of the woodcut allowed for the efficient production of these early prints, making his radical imagery accessible and widely disseminated throughout the European avant-garde.

This piece, preserved in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art, New York, is essential for understanding Kandinsky’s sustained effort to liberate form and color from objective reality. The Vignette next to "Still"? demonstrates the artist’s mastery of graphic media and remains a key component of his broader quest to equate visual language with spiritual necessity.