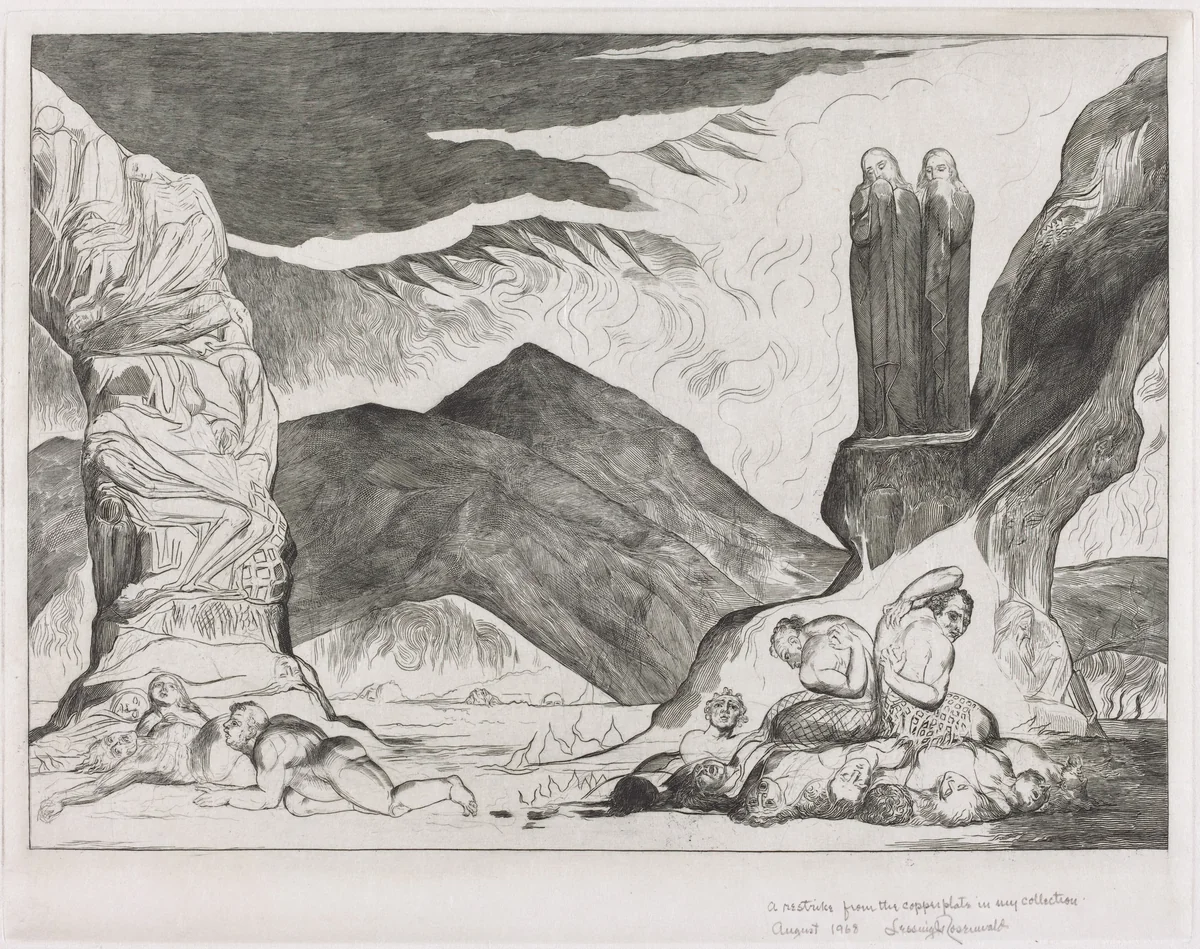

The Circle of the Falsifiers: Dante and Virgil Covering their Noses because of the stench by William Blake; Harry Hoehn is a powerful example of British Romantic illustration, rendered through the exacting medium of engraving. This striking work, dated 1827, depicts a scene from Canto XXIX of Dante Alighieri’s Inferno, specifically the eighth circle (Malebolge), where the souls of the Falsifiers are eternally tormented by hideous disease. The composition centers on the figures of the Roman poet Virgil and Dante, who recoil dramatically, raising their hands to cover their noses against the overwhelming stench that rises from the putrefying souls below. Blake captures the visceral suffering of the damned and the sensory disgust of the travelers, emphasizing the moral consequences of fraudulence described in the epic poem.

The classification of this piece as an engraving [restrike] confirms its complex method of production. Conceived initially by Blake near the end of his life for his celebrated series illustrating Dante’s masterpiece, this particular impression is classified as a restrike. This means the print was pulled later, likely utilizing the original or a meticulously recut plate overseen by Hoehn, the secondary credited artist. The date of the original design places the print firmly within the flourishing period of British print culture between 1826 and 1850. While Blake supplied the initial, complex visionary drawing, Hoehn was instrumental in the technical production necessary to distribute the final prints, resulting in this collaborative attribution. The visual power lies in Blake’s characteristic use of bold outlines and swirling, expressive anatomy, typical of his late work.

As a crucial element of the artist's final body of work, this piece represents one of the most significant endeavors in visionary illustration of the time. The work resides in the permanent collection of the National Gallery of Art, offering scholars important insight into the collaborative artistic practices and intense literary interpretations prevalent in the early 19th century. Due to its historical context and age, this powerful depiction is often recognized as being in the public domain, ensuring widespread access to high-resolution prints for study and preservation worldwide.