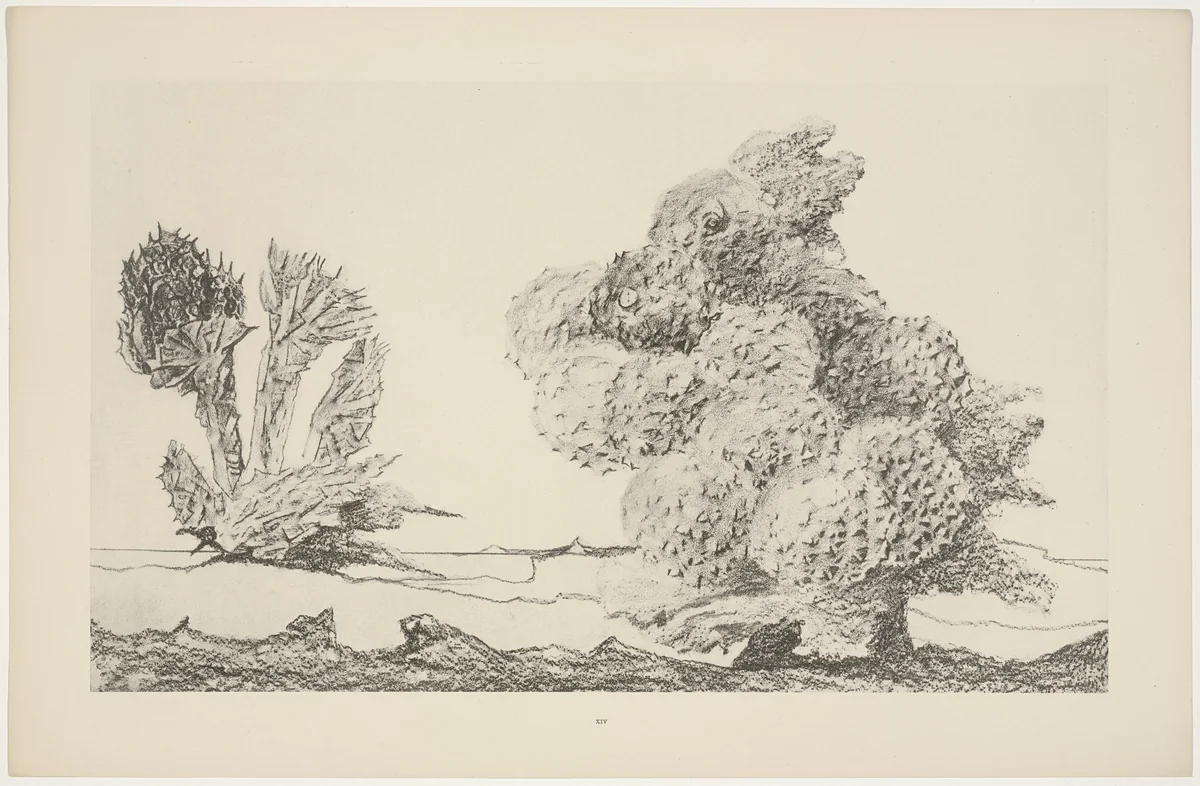

The Chestnut Trees Take-Off (Le Start du châtaignier) from Natural History (Histoire naturelle) is a seminal work by Max Ernst, created circa 1925 and published as part of a landmark portfolio in 1926. This piece exemplifies Ernst’s innovative use of frottage, a technique he invented in 1925 that involves placing paper over a textured surface—such as wood grain, leaves, or netting—and rubbing it with graphite or chalk to capture the pattern. The resulting images are highly textural and often hallucinatory, transforming mundane surfaces into fantastical scenes. The final output, in this case, is a collotype, a high-quality photographic printing process used to reproduce the granular subtlety and enigmatic tone of the original rubbing. This particular print is one of 34 distinct compositions that constitute the complete Histoire naturelle portfolio, a pivotal achievement in the history of Surrealist prints.

Working within the burgeoning Dada and Surrealist movements of French culture, Ernst aimed to bypass conscious control, allowing the emergent forms dictated by the frottage process to guide the creation. The title, The Chestnut Trees Take-Off, suggests an organic metamorphosis where botanical subjects achieve improbable movement. The composition is characterized by dense, swirling lines and fractured textures that abstractly reference wood grain and foliage, but which coalesce into strange, aerial structures. Ernst utilized textures found in commonplace items, thus transforming familiar natural materials into cosmic or volatile elements, blending the terrestrial with the subconscious.

The radical nature of the frottage technique cemented Ernst's status as a leading figure in early 20th-century printmaking. Though created in c. 1925, the subsequent publication of the portfolio in 1926 broadened the influence of the prints on subsequent generations of artists exploring automatism and abstraction. This notable example of Natural History is housed in the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), recognizing its significance to modern art. As influential works of this period increasingly become available through public domain initiatives, the study and appreciation of Ernst’s groundbreaking graphic processes continue to grow worldwide.