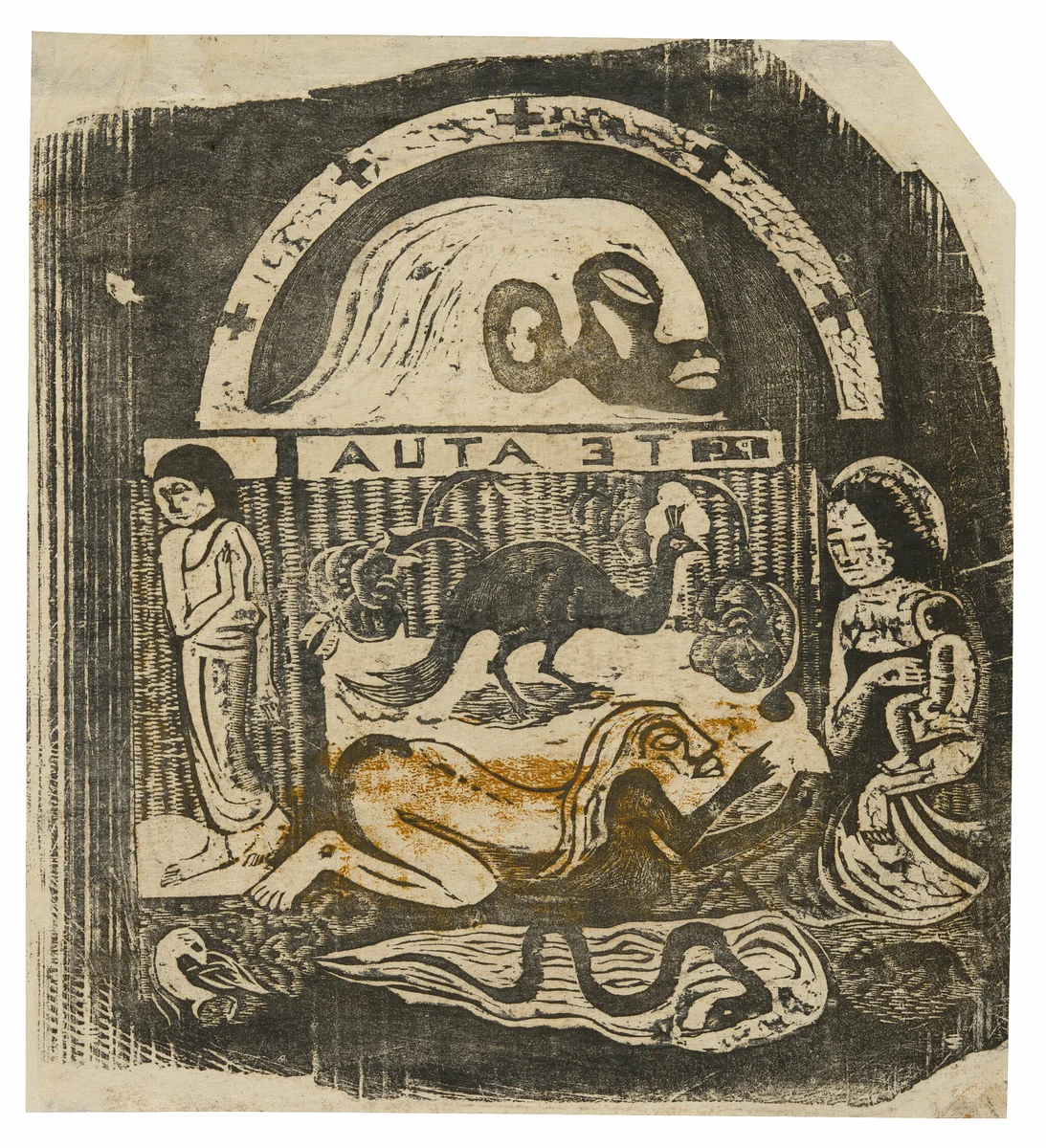

Te atua (The God), from the Suite of Late Wood-Block Prints, created by Paul Gauguin (French, 1848-1903) between 1898 and 1899, is a pivotal example of the artist's late exploration of spirituality and indigenous Polynesian mythology. This complex graphic work demonstrates the radical formal experimentation characteristic of Gauguin’s final years.

The technique involved a meticulous layering process: the image was produced as a wood-block print in black ink, featuring a subtle yellow ocher ink offset, and transferred onto thin ivory Japanese paper. The resulting print was then laid face down on ivory wove paper to create the final recto. Further complicating the work, the verso contains a separate impression-a wood-block print rendered in brownish-black ink on the wove paper support itself. Gauguin’s dedicated, experimental approach to this medium elevated the status of late 19th-century prints in France.

Focusing on themes of divine figures and creation myths, Gauguin used the stark, simplified forms inherent in the woodcut technique to convey a profound sense of primitive power. This stylistic choice, developed by the French master during his time in the South Pacific, solidified his lasting influence on subsequent modernist movements. This significant piece is held in the permanent collection of the Art Institute of Chicago, where it serves as a key reference for scholars studying the artist's printmaking corpus. The enduring importance of works like this ensures their continued relevance, especially as high-quality documentation contributes to the broader accessibility of art in the public domain.