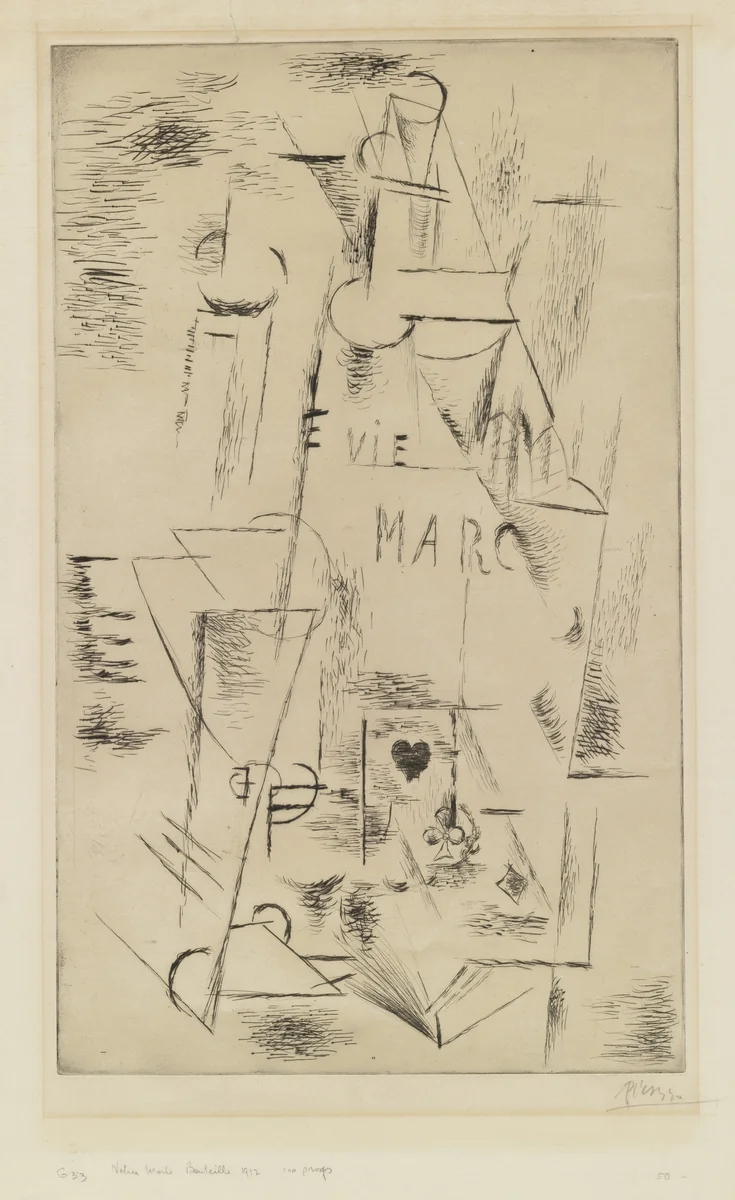

Still Life with Bottle of Marc (Nature morte à la bouteille de marc) was executed by Pablo Picasso in 1911 and published as a print in 1912. This seminal work belongs to the critical phase of Analytical Cubism, a movement Picasso co-founded with Georges Braque, dedicated to systematically deconstructing form and spatial relationships. Unlike his contemporary oil paintings which often employed subtle color variations, this drypoint relies solely on the stark contrast of line and texture to dismantle and reconstruct the subject matter. The work explores the translation of complex three-dimensional forms onto a flat plane using only the reductive process inherent in the intaglio printmaking method.

As a drypoint, Picasso created the image by directly scoring the copper plate with a sharp needle, lifting a characteristic burr that holds ink, resulting in rich, velvety lines when printed. The subject, a bottle of marc (a type of French pomace brandy) situated within a café or studio setting, is fractured into a system of overlapping, transparent planes. This rigorous visual language challenges traditional perspective, requiring the viewer to synthesize multiple viewpoints simultaneously. Picasso’s dense networks of cross-hatching emphasize structure and volume through purely graphic means, highlighting the intellectual rigor of his Spanish output during this key period.

The year 1911 marked a profound exploration of abstraction in Picasso’s career, making this specific image from 1911, published 1912, crucial for understanding the transition toward Synthetic Cubism. This commitment to creating fine art prints allowed Picasso to experiment rapidly with the structural elements of Cubism outside of traditional painting. Today, this key piece of modern graphic arts resides in the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), demonstrating the foundational role of Picasso’s early Still Life with Bottle of Marc within the history of 20th-century Western art.