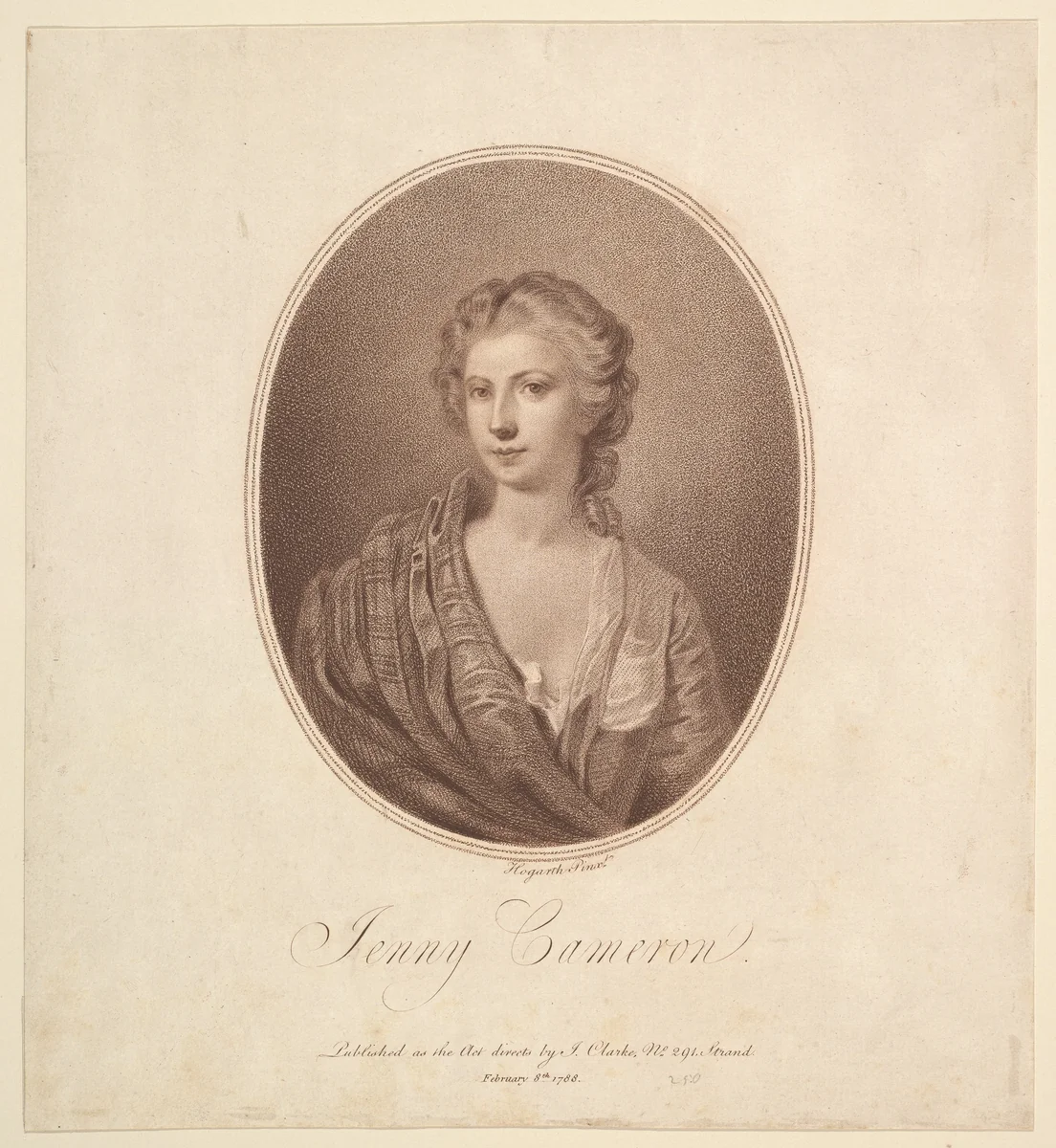

"Jenny Cameron" by William Hogarth, dated 1788, is a refined example of 18th-century British prints. This specific impression, part of The Metropolitan Museum of Art collection, utilizes the meticulous stipple engraving technique. This method, characterized by fine dots used to create tone and shadow, allowed for softer transitions than traditional line engraving, giving the Jenny Cameron portrait a more painterly quality. The choice to print the image in warm brown ink, rather than the standard black, further enhances this subtle, delicate effect, reflecting contemporary shifts in aesthetic preferences for graphic arts.

While Hogarth himself passed away in 1764, the enduring demand for his socially and historically resonant designs ensured the continued production of impressions well into the late 18th century, with secondary engravers executing the plates. Hogarth specialized in political and social commentary, and this depiction contributes to the rich collection of British portraits of prominent women figures, even those whose fame rests on historical mythology. Cameron was a celebrated, perhaps apocryphal, figure associated with the Jacobite uprising of 1745, and her popularity demonstrates the power of inexpensive prints in disseminating romanticized historical narratives and propaganda during the period.

The technique and subject matter place the piece firmly within the context of late Enlightenment graphic arts. Preserved by the Met, the work is frequently studied by scholars of graphic arts, and high-resolution images of this print are often released into the public domain for educational use, ensuring continued access to the legacy of Hogarth. This piece documents the transition in British printmaking from robust etching to the more modulated, tonal effects of stipple engraving.