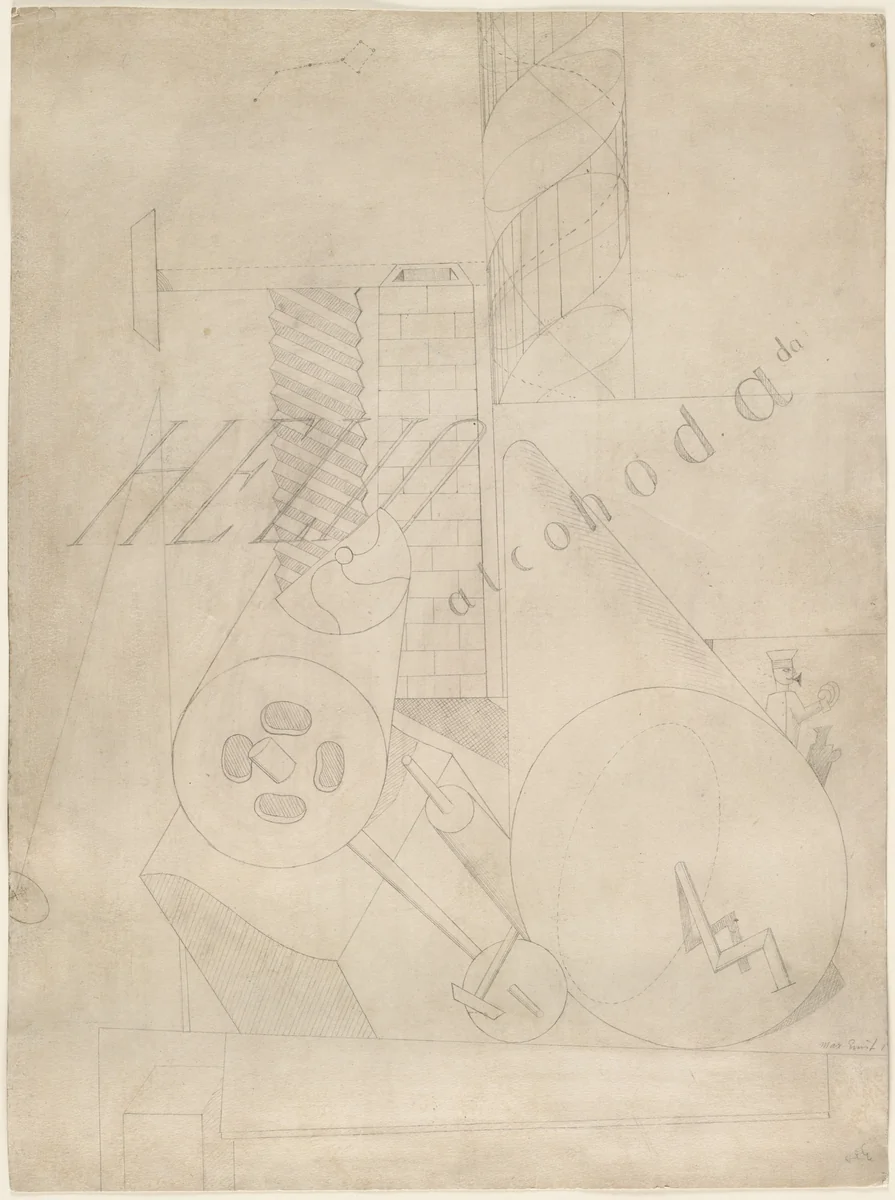

Helio Alcohodada by Max Ernst is a key pencil drawing on paper created in 1919. This important early work provides insight into the artist’s immediate post-war experimentation and his foundational engagement with the emerging principles of Dada. Classified as a drawing, the piece utilizes the delicate medium of pencil to render forms that are fragmented, abstract, and suggestive of mechanical or biological schematics, characteristic of the era’s cynical response to rationalism.

The 1919 period was defined by cultural upheaval across Europe, spurring Ernst, a central figure in the French avant-garde, to reject traditional artistic conventions. This piece is less a depiction of a known scene and more an intellectual exercise in juxtaposing disparate elements. Ernst utilized precision in his draftsmanship, contrasting the careful technical execution inherent in pencil work with the deliberate absurdity of the image’s content. The work embodies the Dada principle of anti-art, employing detailed representation to subvert expected meaning.

Ernst frequently used drawing and collage to develop the irrational narratives that would soon define Surrealism. The composition avoids central focus, compelling the viewer to process the image as a series of unrelated, yet carefully articulated, visual statements. The sensitivity of the medium underscores the conceptual rigor underpinning the artist’s radical thematic concerns during this crucial transitional moment.

This pivotal French drawing resides in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Its preservation ensures access for scholars studying the development of modern art, particularly the years immediately following the Great War. Works from this specific 1919 date are highly valued for illustrating the genesis of Ernst's mature style, and high-quality prints of such drawings are often referenced in academic discourse.