William Ward

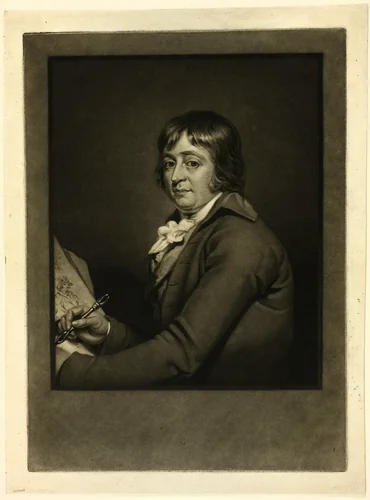

William Ward (active 1775-1822) stands as one of the preeminent English engravers of the Georgian era, celebrated for his mastery of the demanding mezzotint technique. His career spanned nearly five decades, during which he acted as a crucial intermediary, translating the color and texture of contemporary oil paintings and important historical subjects into highly detailed, accessible prints. Ward’s technical precision and tonal sensitivity ensured his work reached not only specialized collectors but also the burgeoning middle-class art market. His historical significance is cemented by the consistent inclusion of his work in prestigious global institutions, including the Rijksmuseum, the National Gallery of Art, and the Art Institute of Chicago.

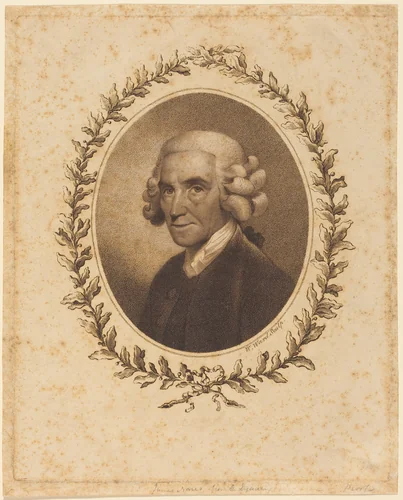

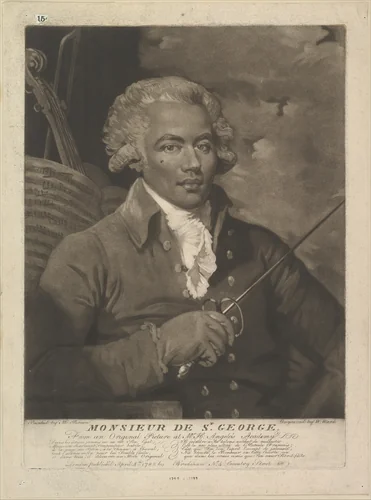

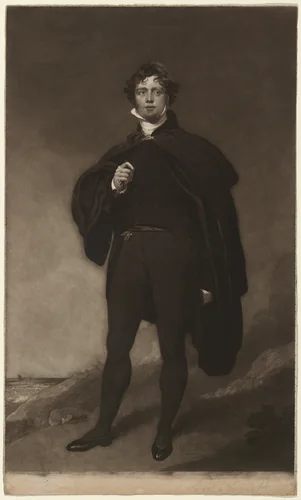

Ward’s output demonstrates an impressive thematic breadth, successfully bridging high portraiture, historical narrative, and lively domestic scenes. He excelled at rendering prominent figures of the day, as seen in his commanding portrait of James Nares and the exotic, powerful depiction of Monsieur de St. George. However, Ward was equally adept at illustrating the intimate or everyday moments of 18th-century life. His genre scenes, such as the vibrant portrayal of social dynamics captured in Inside of a Country Alehouse, demonstrate a sharp observational wit, providing visual documents of a rapidly changing British society.

The versatility of William Ward prints allowed him to shift seamlessly between the poignant historical gravity of works like Mary, Queen of Scots, Under Confinement and the more intimate, domestic focus encapsulated in the Dutch-titled scene, Kraamhulp presenteert de baby aan een man (Midwife presenting the baby to a man). This effortless movement between high drama and quiet realism underscores his commercial and artistic acuity. The sheer range of subjects he tackled perhaps reveals less a focused artistic vision than a highly pragmatic response to the public's appetite for visual media.

In an age before photography, Ward’s engravings were fundamental in disseminating artistic ideas and historical knowledge. His skillful craftsmanship ensured these documents of history and art were preserved, and today many of these museum-quality reproductions are available as high-quality prints. Thanks to this legacy, much of Ward’s historical catalogue is now in the public domain, securing his position not merely as a technically proficient artisan, but as an essential figure in the visual history of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.