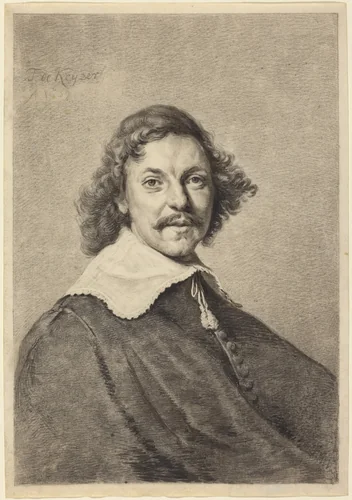

Thomas de Keyser

Thomas de Keyser (c. 1596-1667) stands as one of the pivotal figures in Dutch Golden Age portraiture, representing the pinnacle of Amsterdam’s artistic output in the 1620s and early 1630s. Working across a prolific period that spanned nearly four decades, his distinctive style bridged the detailed realism of earlier Dutch masters with the dramatic psychological insight that would define the mid-century.

Initially trained under his father, the architect and sculptor Hendrik de Keyser, Thomas carved out a highly specialized niche in the fiercely competitive Amsterdam market. His reputation was built largely on his innovative approach to the full-length portrait. Rather than adhering to the large, formal scale preferred by contemporaries, De Keyser often utilized a smaller canvas, allowing him to place his sitters in dynamic, realistic interior settings. This technique created an unprecedented sense of intimacy and immediacy, visible in commissioned works such as Portrait of Loef Vredericx (1590-1668) as an Ensign and the powerful civic piece, Groepsportret van een onbekend college.

For a decade, De Keyser was the undisputed leader in Dutch portrait commissions, providing elegant character studies exemplified by the pair, Portrait of a Man with a Shell and Portrait of a Woman with a Balance. His market dominance abruptly ceased around 1632, coinciding with the explosive emergence of Rembrandt van Rijn, who, while eclipsing De Keyser in subsequent decades, was demonstrably influenced by his technical facility, particularly his sophisticated handling of light and texture.

Interestingly, while navigating the demands of elite artistic patronage, De Keyser maintained a parallel career as a dealer in Belgium bluestone and a stone mason—a rare instance of an artistic powerhouse balancing high-end commissions with the trade of construction materials. The lasting quality of his output proved so high that, long after his death, many of his finest Thomas de Keyser paintings were mistakenly or opportunistically reattributed to Rembrandt. This persistent confusion serves as a powerful, if complicated, tribute to his mastery.

Today, his refined portraiture is highly valued by global institutions, including the Rijksmuseum and the National Gallery of Art. Enthusiasts often seek out high-quality prints and studies of his work, now readily available as downloadable artwork in the public domain.

Source: Wikipedia · CC BY-SA 4.0