Thomas Annan

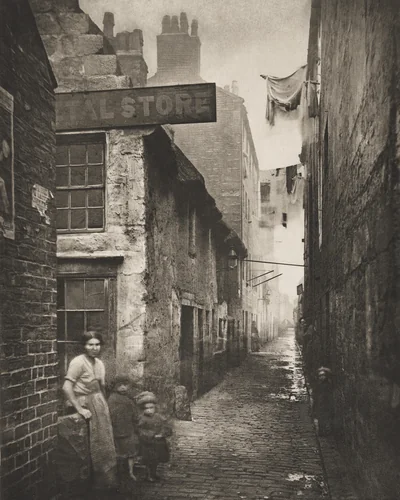

Thomas Annan (1829–1887) is recognized as a pioneering figure who fundamentally shifted the purpose of photography from artistic representation and portraiture toward direct, systematic social documentation. The Scottish photographer holds the distinction of being the first to employ the camera extensively and systematically to catalogue the squalor of urban poverty, effectively transforming the medium into a powerful instrument for municipal reform.

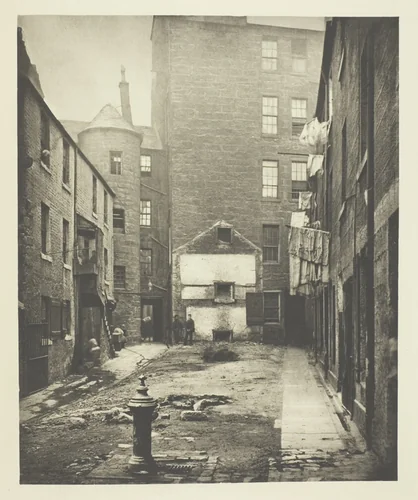

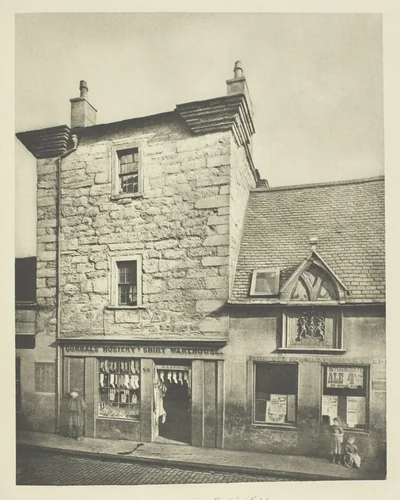

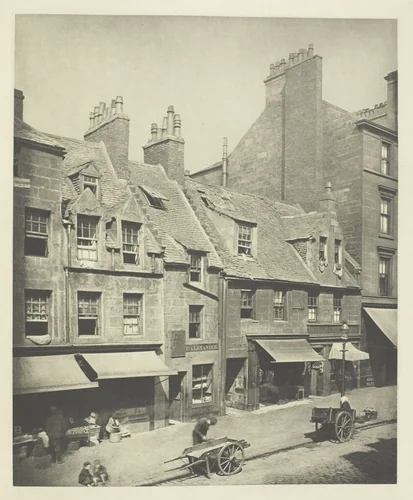

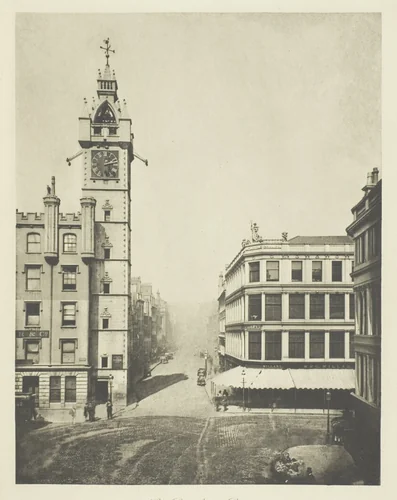

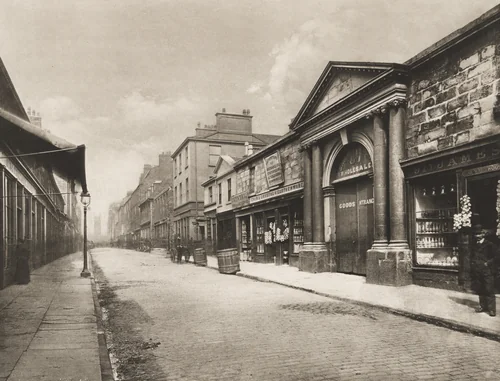

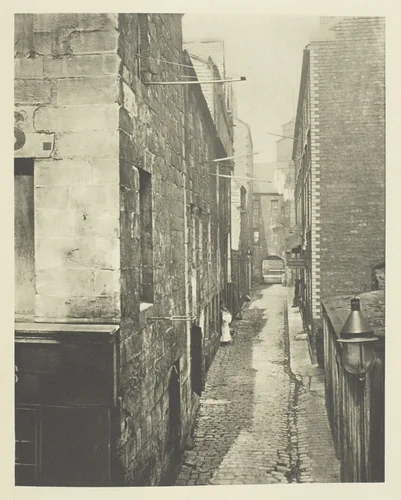

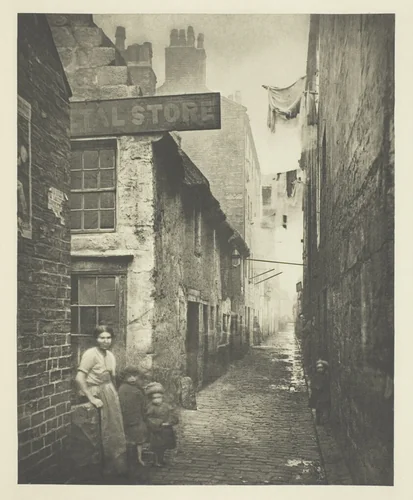

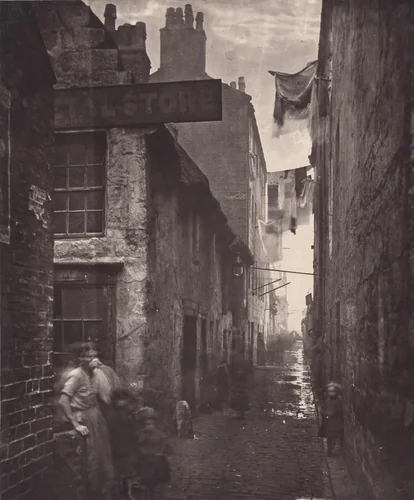

Annan’s most significant body of work, captured primarily between 1867 and 1868, centers on the densely packed, deteriorating closes and courts of Glasgow. These photographs were often commissioned as part of civic plans to justify the demolition of slums under the City Improvement Act. Far from mere aesthetic studies, images like Bell Street from High Street and Broad Close No. 167 High Street function as precise, unvarnished architectural records. Annan’s technical skill allowed him to navigate the notoriously poor light of these narrow, sunless passages, producing images characterized by their grim clarity and uncompromising factual gaze. This focus on detail elevated the photographs beyond simple records, endowing them with lasting social and artistic weight.

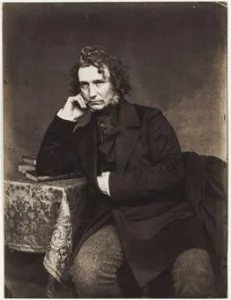

While Annan maintained a highly successful commercial practice specializing in high-quality portraiture—including a notable early study, Portrait of D.O. Hill—it is the grueling series documenting urban blight that defined his legacy. This duality of professional focus, running a profitable studio while simultaneously capturing the city’s most desperate margins, speaks to a deeply committed, yet pragmatic, artistic approach.

His work was groundbreaking both in its subject matter and its direct application to governmental policy, providing an objective visual argument for sanitation and clearance. Today, Annan’s photographs are celebrated as early masterpieces of documentary realism, residing in major institutional collections, including the Museum of Modern Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Their status as museum-quality historical documents remains undisputed. Furthermore, many of these iconic plates have entered the public domain, ensuring scholars and enthusiasts worldwide can access and study the history and craft through readily available downloadable artwork and high-quality prints.

Source: Wikipedia · CC BY-SA 4.0