Robert Blyth

Robert Blyth occupies a fascinating, if fleeting, niche in late eighteenth-century graphic arts. Active for a remarkably short period, spanning approximately 1778 to 1780, his compact output of just fifteen known prints achieved significant institutional recognition, with examples now held in major international venues, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art. While the printmaker’s precise biographical details remain elusive, the focused energy of his graphic production speaks volumes about the popular tastes, narrative anxieties, and commercial circulation of imagery in the period.

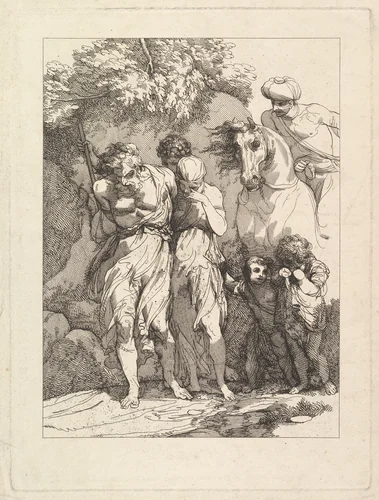

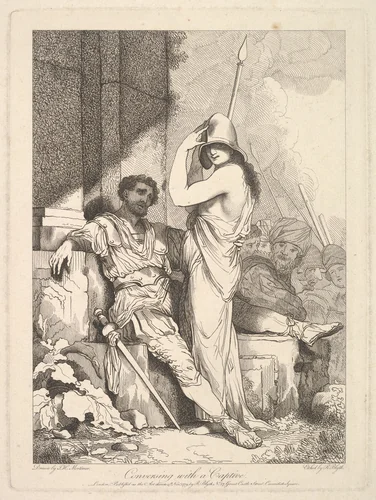

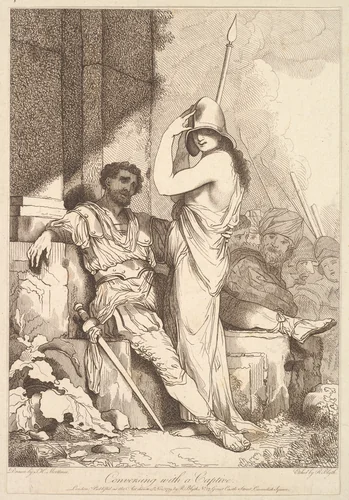

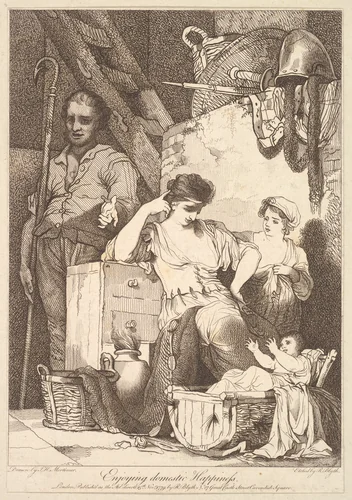

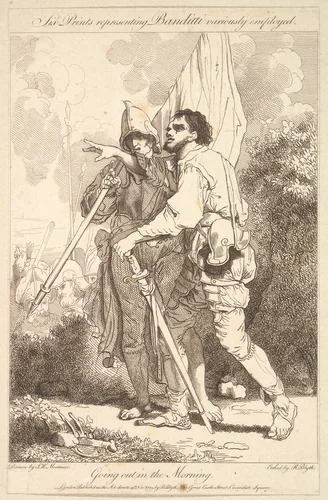

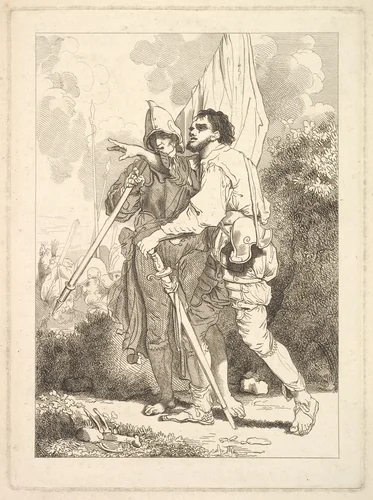

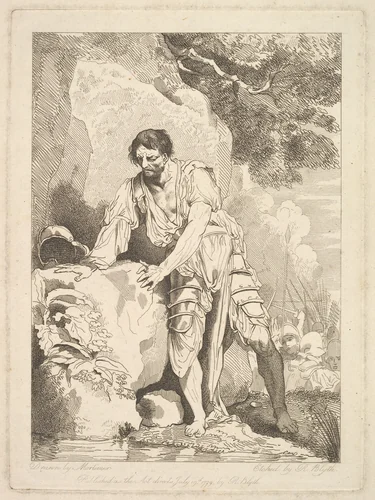

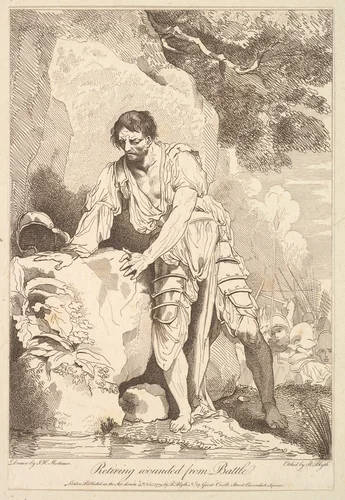

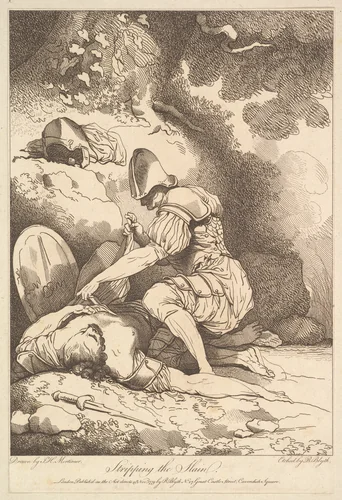

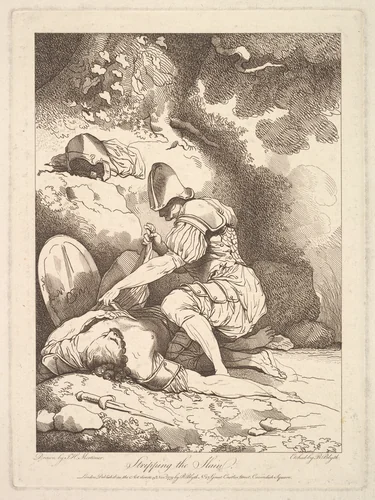

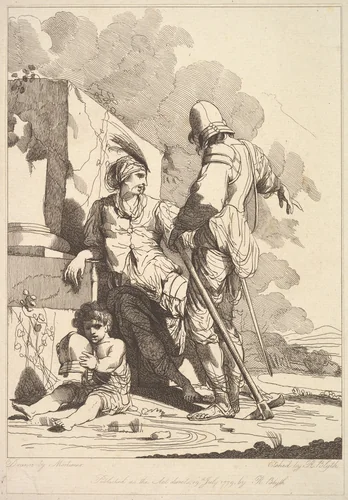

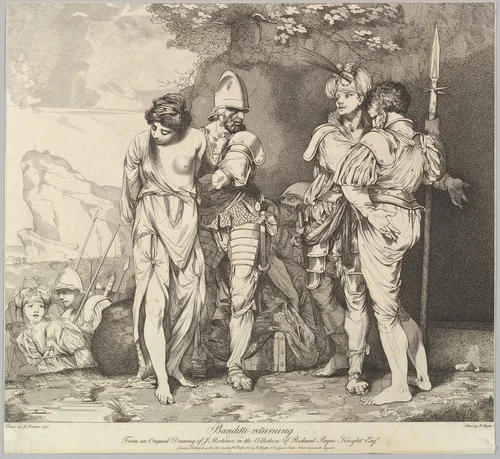

Blyth’s work concentrated heavily on dramatic, often exoticized, subjects, focusing on themes of conflict, captivity, and outlaw life. Central to his known corpus is the series Banditti Variously Employed, which portrays the bandit figure not merely as a symbol of violence, but as part of a complex, almost theatrical social structure. Titles such as Conversing with a Captive and Enjoying Domestic Happiness reveal a deliberate tension, romanticizing the brigand by juxtaposing acts of menace with scenes of unexpected, if unstable, domesticity. This careful visual structuring positioned Blyth squarely within the contemporary European fascination for picturesque ruins and romanticized conflict, a trend that provided rich material for high-quality prints circulated widely across Britain and the continent.

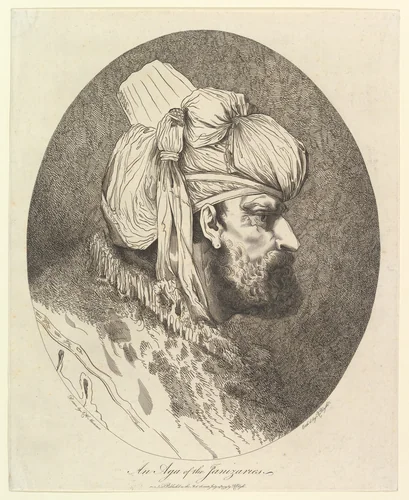

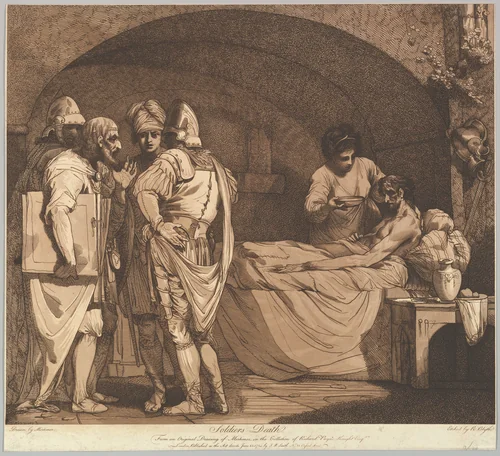

Operating primarily in the medium of reproductive graphic arts, Blyth contributed effectively to the flourishing market for downloadable artwork and affordable visual narratives. His print An Aga of the Janizaries, for instance, showcases a keen eye for military detail and costume design, reflecting the era's growing documentary interest in foreign militaries and geopolitical subjects. The artist’s facility for drama also extended to more intimate and desperate scenarios, as seen in the poignant composition A Captive Family.

Although his career seemingly vanished as quickly as it materialized, the fact that his limited catalogue ranges from formidable military officers to scenes of domestic despair suggests an artist highly adept at capitalizing quickly on diverse, popular narrative demands. It is perhaps the greatest irony of Blyth’s brief artistic trajectory that this recognized master of visual melodrama chose to remain silent regarding his own life story. Today, many of these Robert Blyth prints are available in the public domain, ensuring that these small, museum-quality examples of late eighteenth-century graphic storytelling continue to be studied and appreciated long after the artist’s intense, three-year moment in the spotlight.