Picardy

The Master known only as Picardy, active during the crucial transitional period spanning 1475 to 1490, remains central to understanding late medieval painting in northern France. This appellation, which reflects the historical and cultural territory from which the artist likely hailed, points to a period when the province was formally establishing its identity within the larger French structure.

The geographical region of Picardy, unlike its neighbors Normandy, Brittany, or Champagne, was never established as a formal duchy or principality. Its boundaries notoriously fluctuated over the centuries due to persistent political instability, a fitting historical metaphor for an artist whose personal identity remains frustratingly elusive to modern scholars. While the first official recognition of the province dates back to the 13th century through the University of Paris, and it entered the French administrative system in the 14th century, the master’s name serves as a geographic placeholder rather than a definitive signature.

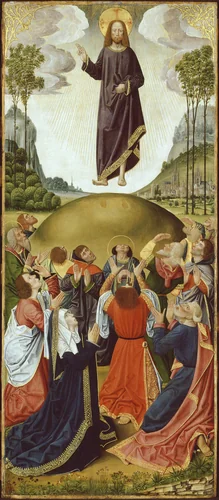

Picardy’s surviving oeuvre, though limited to seven documented works, is defined by significant devotional commissions, primarily for the Charterhouse of Saint-Honoré near Thuison-les-Abbeville. The high-quality panels from the High Altar demonstrate a profound competence in sacred narrative, particularly the psychologically intense depiction of The Last Supper and the dynamically structured Pentecost. Further works include altarpiece panels focusing on local piety, such as the sober renderings of Saint Honoré and Saint Hugh of Lincoln, alongside the celestial movement captured in The Ascension. These Picardy paintings showcase a meticulous handling of detail, an acute sensitivity to atmospheric light, and a clear adoption of Netherlandish techniques permeating Northern French workshops during this late 15th-century moment.

Though the historical region of Picardy officially merged into the new region of Hauts-de-France in 2016, the Master’s artistic legacy endures in major international collections, most notably represented by works held at the Art Institute of Chicago. These rare examples are considered museum-quality artifacts, and scholars frequently seek high-quality prints of the Thuison-les-Abbeville commissions, ensuring the intricate details of this formative period in European religious art remain accessible for study and appreciation.