Matthew Pratt

Matthew Pratt (1734-1805) holds a pivotal position in the development of painting traditions in the American Colonies, establishing himself as a premier portraitist famous for documenting the mercantile and landowning elite of the pre-Revolutionary Era. Active prominently between 1764 and 1774, Pratt’s works provided a clear, factual visual record of American men and women seeking to project status and refinement through European-derived stylistic norms.

Trained in Philadelphia and later refining his technique under Benjamin West in London, Pratt became an early American exemplar of professional artistry. His individual portraits, such as the compelling Christiana Stille Keen and Mrs. Peter De Lancey, display a clarity and formality typical of mid-eighteenth-century colonial commissions. These Matthew Pratt paintings showcase his meticulous attention to textile detail and facial expression, establishing the sitters’ seriousness and position within society.

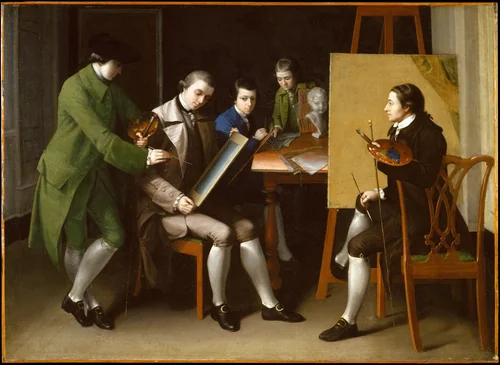

Pratt’s most historically significant contribution is perhaps the genre scene, The American School (c. 1765). This work, celebrated today as one of the earliest depictions of American artists practicing their craft, visualizes the professional training received by American painters studying abroad. While the title suggests a fully established educational institution, the painting offers a charming glimpse into the informal, yet rigorous, studio environment under West in London, effectively depicting the moment when the foundations for an independent American style were being laid by practitioners returning from Europe.

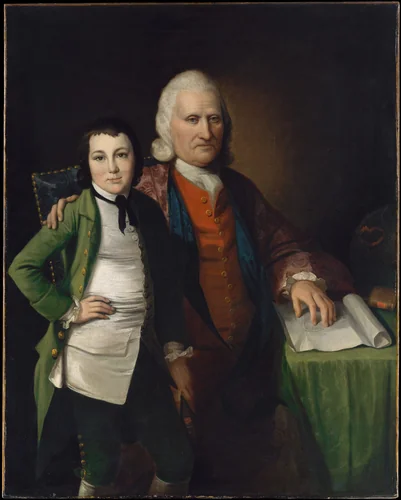

The legacy of Pratt is secured through the continued study of his output. Examples of his work, including Reynold Keen and the surprising mythological subject Madonna of Saint Jerome, are housed in major institutions such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the National Gallery of Art. These museum-quality works define the early artistic tastes of the colonies. Due to their significance and age, many of Pratt’s foundational images now reside in the public domain. This allows scholars and enthusiasts worldwide to access these important visual documents; the works are often available as high-quality prints and downloadable artwork, ensuring the integrity of the colonial record remains accessible for continuous appreciation.