Louis Le Nain

Louis Le Nain, operating within 17th-century France, was one of three artist brothers, alongside Antoine (c.1600–1648) and Mathieu (1607–1677), who collectively revolutionized the representation of everyday life. Working primarily in Paris, the Le Nains developed a style defined by stark realism and an unadorned focus on the human subject. Their collective oeuvre, spanning genre scenes, refined portrait miniatures, and full-scale portraits, offered a quiet but profound counterpoint to the dramatic baroque sensibilities that dominated the era’s academic art.

While the difficulty of definitively attributing specific works to a single brother has long fueled scholarly debate, Louis is generally credited with the most evocative and enduring genre pieces. He abandoned the typical moralizing or comic treatment of lower-class subjects prevalent at the time, instead depicting peasants with remarkable solemnity and dignity. Works such as Peasant Interior are characterized by muted tonality and a compositional gravity that elevates the subject matter, transforming simple laborers into monumental figures observed in moments of quiet contemplation. This commitment to sincere observation distinguishes the Louis Le Nain paintings as historically significant, setting a precedent for realistic social commentary in European art.

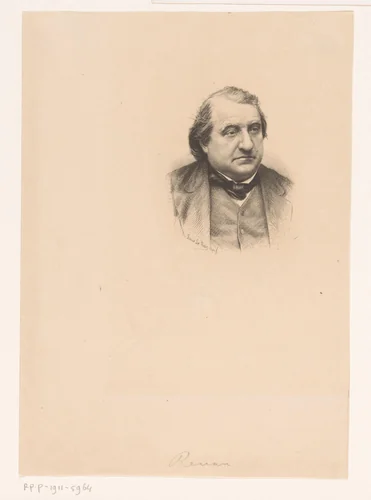

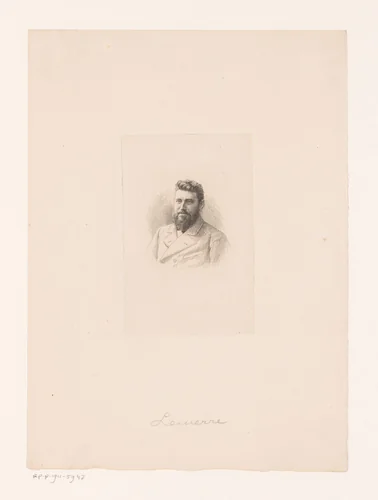

The technical diversity of the brothers’ output ensured their enduring impact. Beyond oil on canvas, their influence was maintained through various forms of reproduction, resulting in numerous Louis Le Nain prints that documented their innovative approach to portraiture. This tradition continued centuries later, as evidenced by associated works such as Portret van Ernest Renan. Louis’s career ended abruptly with his death in 1648, yet the collective vision of the Le Nains solidified a major contribution to French artistic heritage.

Today, the work of the Le Nain brothers is preserved in the permanent collections of pre-eminent institutions, including the Rijksmuseum and the National Gallery of Art. The accessibility of these masterworks means that a significant portion of their output is now in the public domain, allowing for the widespread creation of high-quality prints, ensuring that the serene realism of 17th-century France remains widely accessible to modern audiences.