Karl Blossfeldt

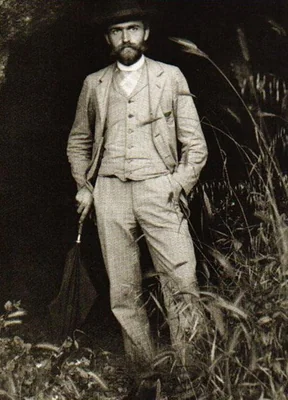

Karl Blossfeldt (1865-1932) was a pivotal German photographer and sculptor whose exacting focus on natural forms fundamentally influenced the early twentieth-century visual environment. While his earliest works date back to 1898, his enduring reputation rests squarely on the 1929 publication Urformen der Kunst (Art Forms in Nature). This extraordinary collection of close-up, highly magnified plant studies provided a rigorous, comparative morphology of the botanical world, instantly cementing Blossfeldt’s position among the pioneers of Modernist photography.

Blossfeldt’s aesthetic project was deeply rooted in the structural symmetries and growth patterns observed in nature, a commitment he shared with his own father. As a professor at the School of the Museum of Applied Arts in Berlin, Blossfeldt created his photographs initially as instructional aids. He required teaching materials that demonstrated the raw, inherent design elements of living things, arguing that these perfect, fundamental structures could be endlessly translated into architecture, sculpture, and applied arts.

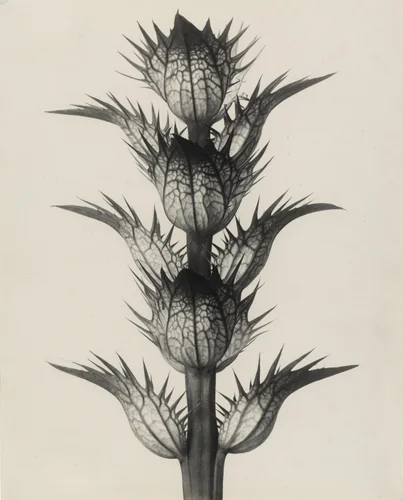

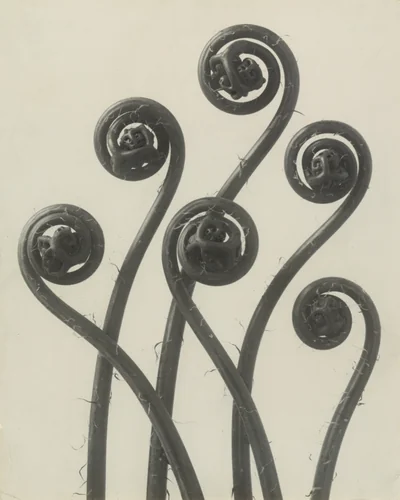

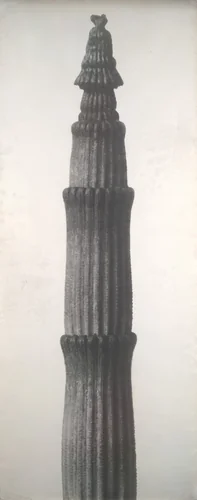

His images, such as the tightly coiled spiral of Adiantum pedatum or the geometrically precise rings of Equisetum hyemale (Rough Horsetail Enlarged 25 Times), are defined by shadowless clarity and monumental scale. Blossfeldt used custom-built cameras to achieve extreme magnification, meticulously isolating specific parts—bracteoles, seed pods, or tendrils—to reveal their inherent aesthetic qualities. The resulting visual paradox—a massive, almost alien form captured with objective precision—is what gives his work its hypnotic authority. One might even suggest that Blossfeldt treated the plant kingdom not as a subject for study, but as an inexhaustible, pre-modernist design studio.

Blossfeldt successfully bridged the gap between scientific record and pure artistic expression, aligning his work with the New Objectivity movement of the Weimar Republic. Today, his striking compositions are recognized as museum-quality examples of photographic innovation, held in collections such as the Museum of Modern Art. Many of his pioneering works are now in the public domain, ensuring that this high-quality vision remains accessible globally through downloadable artwork, continuing to inform designers and artists nearly a century later.

Source: Wikipedia · CC BY-SA 4.0