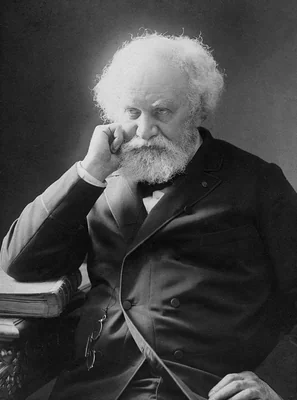

Jules Janssen

Pierre Jules César Janssen (1824-1907), universally known as Jules Janssen, stands as a pivotal figure bridging nineteenth-century astrophysics and early conceptual photography. Though primarily a French astronomer, his relentless scientific methodology demanded the meticulous recording of celestial phenomena, resulting in visual documents of profound aesthetic and historical value. Alongside the English scientist Joseph Norman Lockyer, Janssen is historically recognized for identifying the gaseous nature of the solar chromosphere. Furthermore, his observational work supplied the initial evidence that eventually led to the official identification of the element helium.

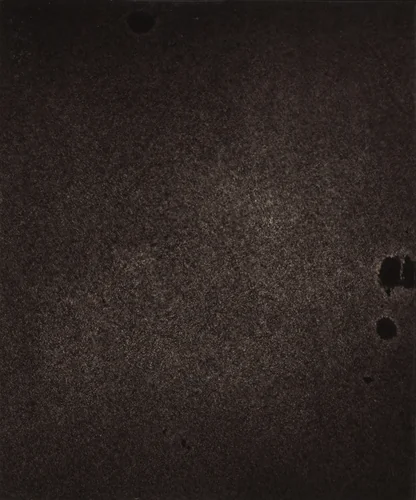

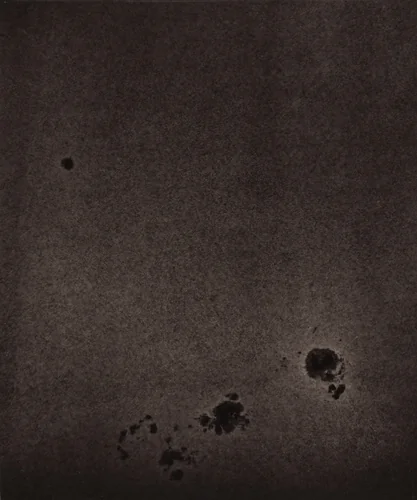

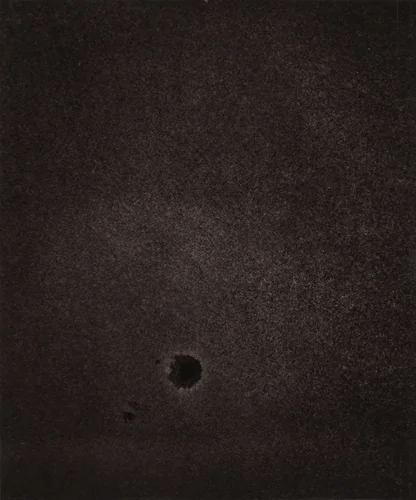

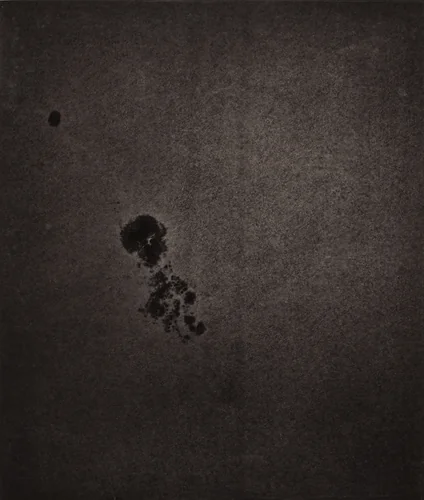

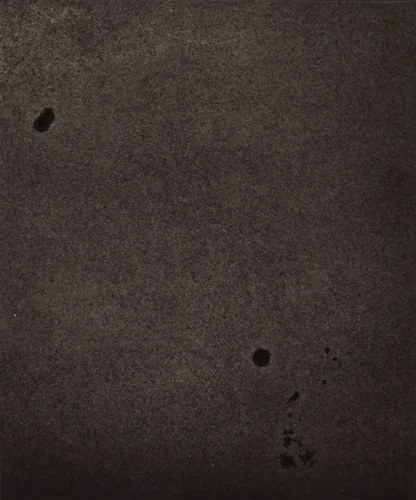

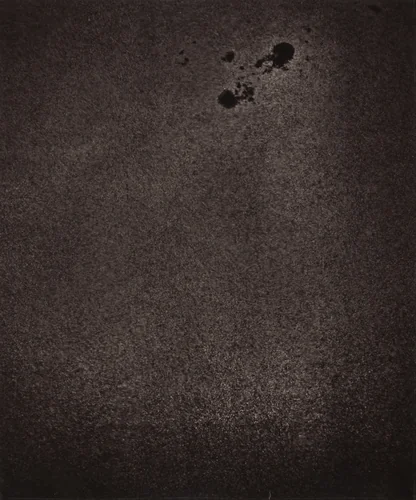

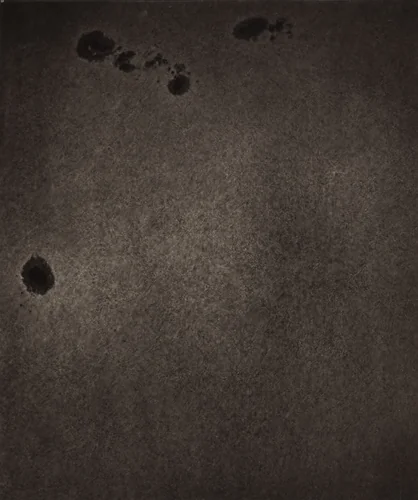

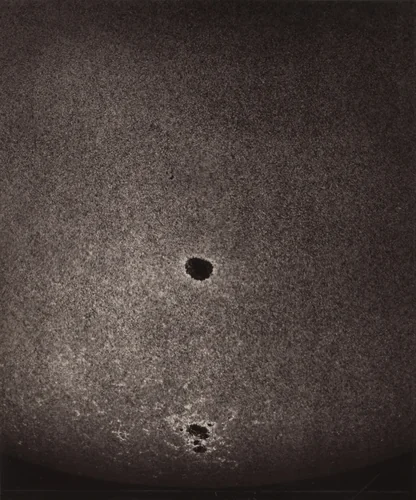

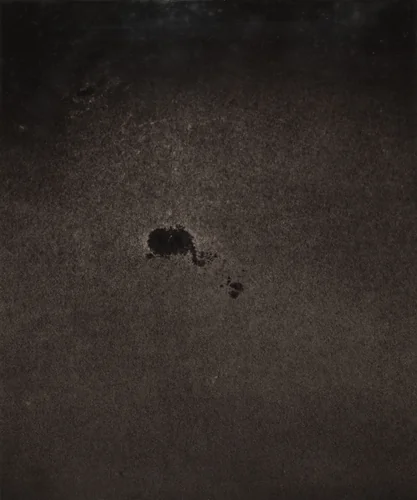

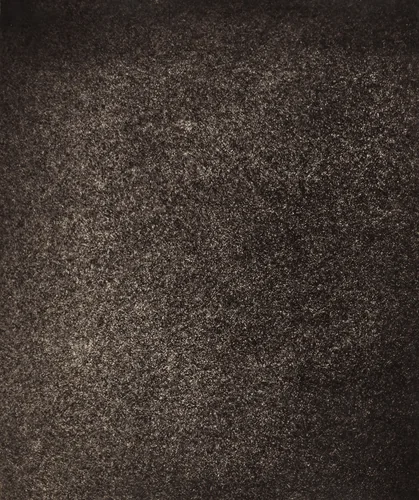

Janssen’s visual legacy is derived from his systematic photographic process, which treated the solar surface not merely as a subject of study, but as an ever-changing object requiring absolute temporal fixation. His collected photographic works, encompassing around fifteen known images, function as rigorous records of light and texture. Works such as the series known as Région Central (Granulations), or the specific capture Région Centrale (Grand Réseau) from August 5, 1877, challenge the boundaries of scientific illustration, presenting the abstract geometry of the cosmos with undeniable artistic force. The extreme focus required to register these delicate, fleeting solar patterns transforms the resulting images into compelling studies of form and negative space.

Active throughout the late 1870s and 1880s, Janssen’s output is highly prized today, with examples held in major international institutions, including the Museum of Modern Art. These museum-quality artifacts are crucial indicators of the burgeoning relationship between early imaging technology and objective observation. What is perhaps the most enduring and subtly eccentric element of the photographs cataloged under Jules Janssen prints is the almost absurd precision of his notation. The recordings, such as Région Central (Granulations), July 8, 1885, were marked not just by date but by the exact hour, minute, and ten-second increment (7h 22m 10s). This insistence on total temporal accuracy defines the essence of the work, fixing a transient cosmic moment forever in time. Today, due to their importance to both scientific and visual history, these historically valuable documents are widely available as downloadable artwork accessed through public domain collections.

Source: Wikipedia · CC BY-SA 4.0