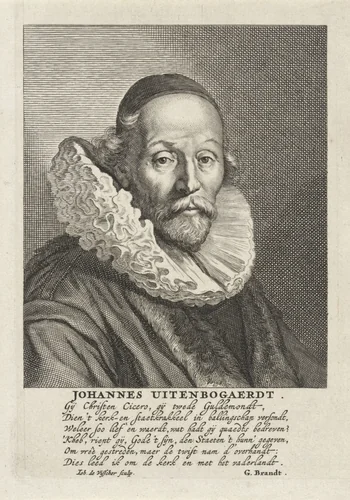

Jan de Visscher

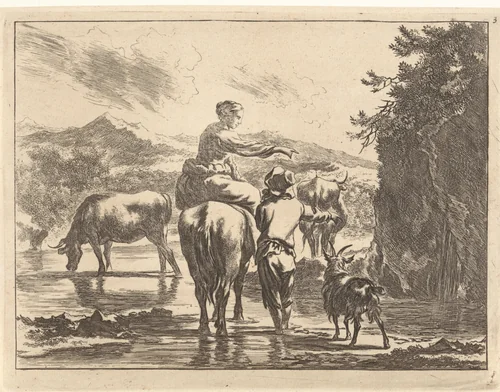

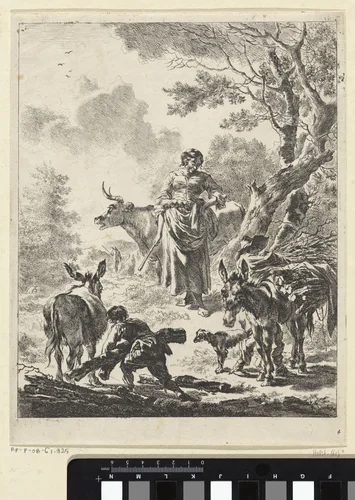

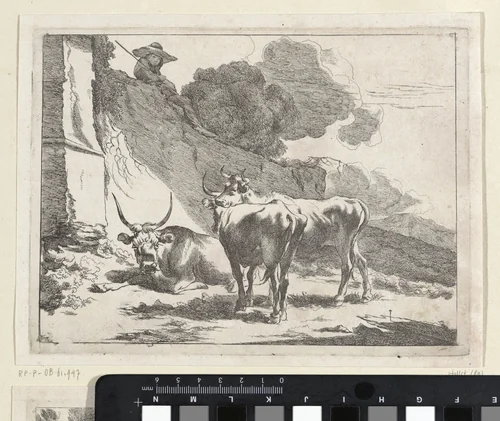

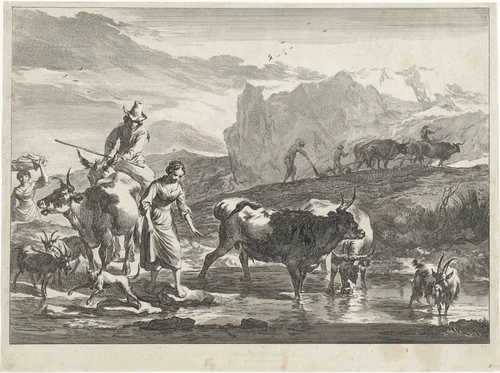

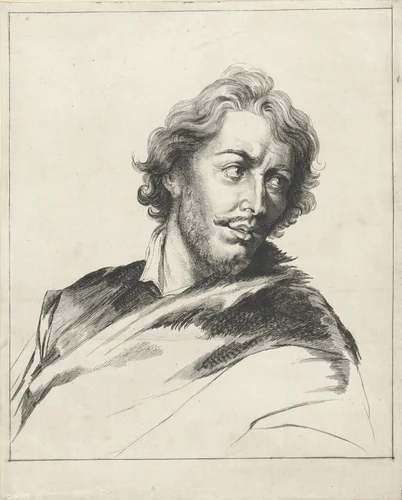

Jan de Visscher (active c. 1643) holds a significant, if often understated, position among the Dutch Golden Age printmakers. Known primarily for his precise and evocative engravings, Visscher contributed substantively to the flourishing tradition of graphic arts that defined 17th-century Netherlandish visual culture. His early career was dedicated almost entirely to the copper plate, establishing a repertoire that spanned robust genre scenes and complex religious narratives.

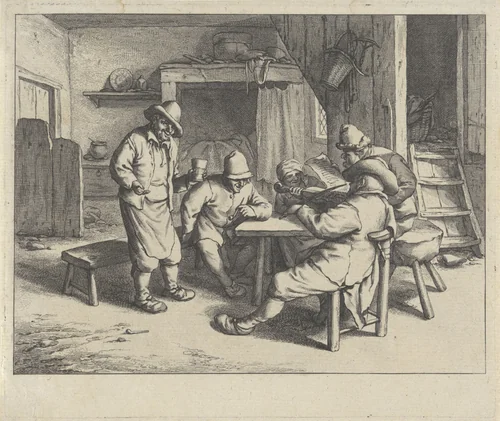

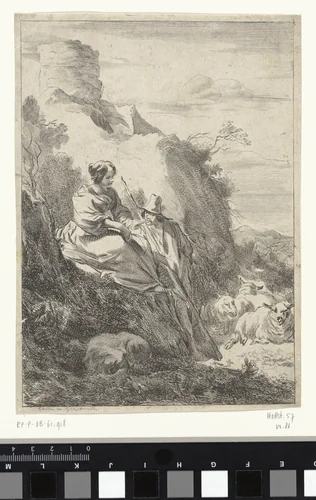

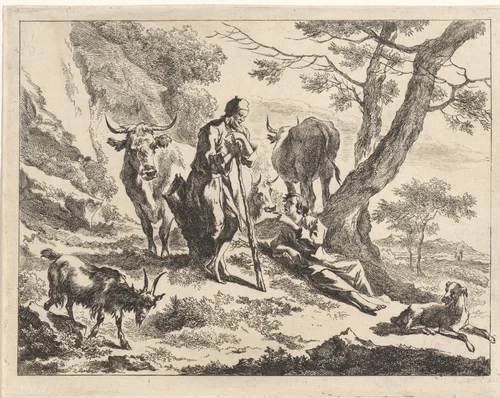

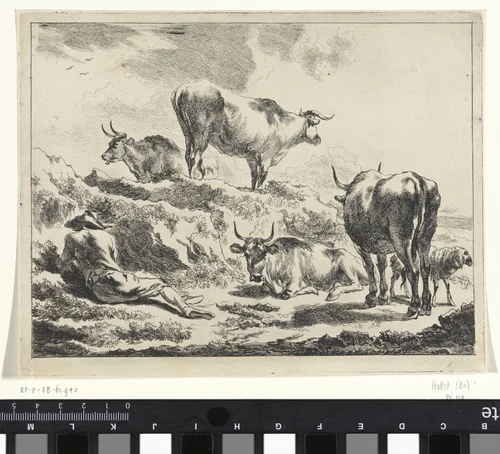

Visscher’s technical skill is evident in the clarity and detail of his compositions. Works such as the lively Boerenbruiloft (Peasant Wedding) and the studies titled Boerendans capture the energy and rough humor of common life, aligning him stylistically with contemporary masters who prioritized quotidian observation. Yet, his practice was not solely focused on the earthy and secular; the complexity of his religious works, including the ambitious Christus geneest een man bij het bad van Betesda, demonstrates his capacity for handling large-scale narrative and sophisticated spatial arrangement. He possessed a keen eye for architectural instability, a characteristic sometimes noted in prints such as Bouwvallige brug (Dilapidated Bridge).

It is perhaps a minor curiosity that an artist who devoted so much energy to detailing the permanence of the etched line would choose, in his later years, to pivot toward the fluidity of oil paint, signaling a quiet shift in professional ambition. While biographical details regarding his transition to painting remain scarce, his initial contribution as an engraver secured his historical footprint.

Visscher’s graphic oeuvre, comprising at least fifteen cataloged prints, provides a valuable record of both Dutch social life and the printmaking innovation of the period. Today, his work is conserved in major international institutions, most notably the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, ensuring the preservation of these museum-quality compositions. The enduring interest in Jan de Visscher prints is aided by the availability of much of his graphic output in the public domain, offering historians and enthusiasts access to high-quality prints and downloadable artwork long after the copper plates themselves fell silent.