Hans Memling

Hans Memling (active 1465–1484) stands as a pivotal figure in the second generation of Early Netherlandish painting, succeeding the foundational masters and establishing Bruges as a leading European artistic center in the late 15th century. Born in the Middle Rhine region, he likely spent his early years in Mainz before moving to the Low Countries for his formal training.

His career was profoundly shaped by his time in Brussels, where he is believed to have worked in the influential studio of Rogier van der Weyden. This critical apprenticeship provided Memling with the stylistic template for refined draftsmanship, meticulous detail, and an emphasis on psychological depth in portraiture. By 1465, Memling was formally established as a citizen of Bruges, where he quickly ascended to become the city’s leading master, overseeing a large and productive workshop.

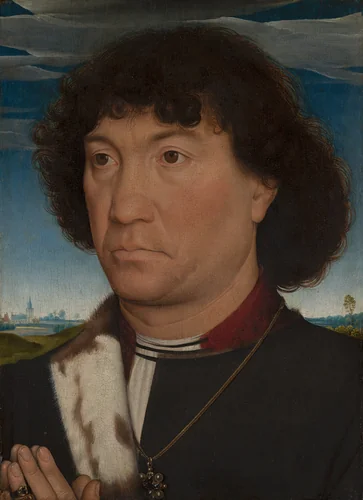

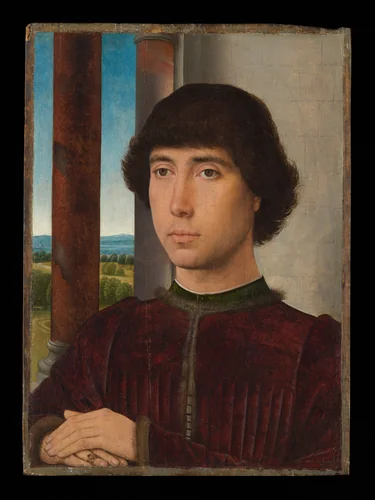

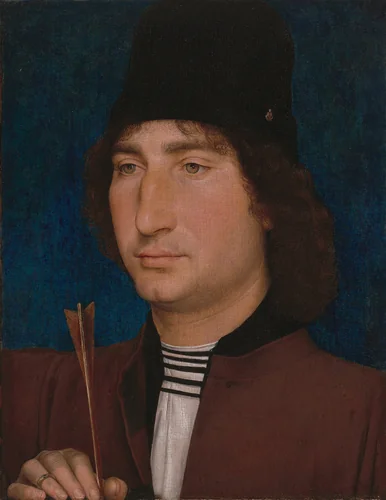

Memling’s output was characterized by commissioned religious works, such as The Annunciation, which often provided the setting for sophisticated and meticulously rendered donor portraits. These portraits, depicting his powerful clientele of clergymen, aristocrats, and affluent burghers, built upon the styles he learned in his youth, offering precise and individualized likenesses framed by rich textures and landscapes.

His success was not merely artistic. A surviving municipal tax document from 1480 lists Memling among the wealthiest citizens of Bruges, a subtle but revealing detail confirming that artistic supremacy could translate directly into considerable financial stature in the nascent Renaissance economy.

Memling’s quiet command of oil paint and his ability to convey narrative through serene, balanced compositions ensured his broad renown across Europe, exporting his style to Italy, Germany, and Spain. His refined technique is evident in singular works like Portrait of a Young Man and Portrait of a Man with an Arrow. Today, these enduring Hans Memling paintings and others are cornerstone holdings in major collections globally, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the National Gallery of Art. Through increasingly available digitized collections, high-quality prints of his iconic works continue to circulate, allowing scholars and the public access to the visual lexicon of the late medieval era.

Source: Wikipedia · CC BY-SA 4.0

![Chalice of Saint John the Evangelist [reverse] by Hans Memling, painting, 1470-1475](https://img.artbee.org/7fc472d8-8a9a-4ce0-891e-2c17ec783e86/small.webp)

![Saint Veronica [obverse] by Hans Memling, painting, 1470-1475](https://img.artbee.org/9d77ece7-b5da-4d75-ae01-e7cac22bbe6c/small.webp)