Hakuin Ekaku

Hakuin Ekaku (1686-1768) is universally recognized as the central figure responsible for the revitalization of the Japanese Rinzai school of Zen Buddhism following a period of nearly century-long spiritual and doctrinal stagnation during the Edo era. While his impact was primarily theological and pedagogical, his prolific output of ink paintings and calligraphy elevates him to the status of a major artistic innovator, using the brush as a direct extension of his rigorous teaching.

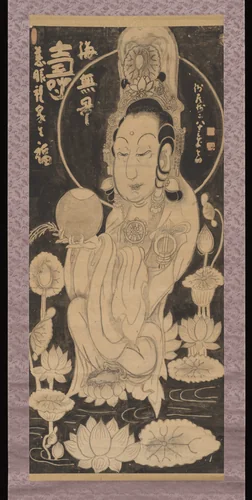

Hakuin’s legacy rests upon a systemic return to intense, integrated training, focusing particularly on disciplined meditation and the demanding intellectual challenge of koan practice. He insisted that the ultimate concern of Zen training was bodhicitta, the dedicated practice of compassion and action for the benefit of others, a spiritual mandate he conveyed visually through his art.

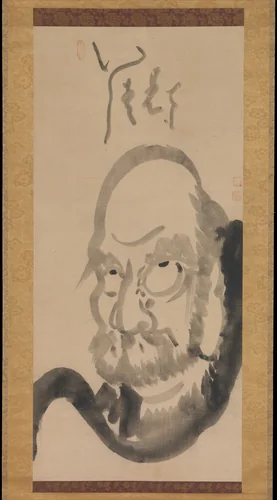

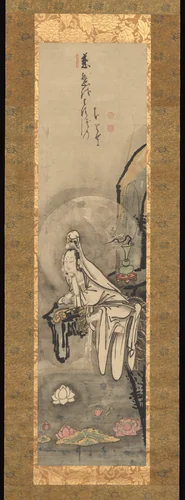

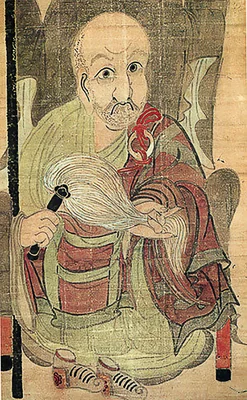

His painting style eschewed the high refinement of academic tradition, favoring a robust, sometimes deceptively naive aesthetic known as zenga (Zen painting). This directness ensured that his visual sermons were immediately accessible, communicating complex spiritual concepts with economy and vigor. His subjects often included simplified renderings of Zen patriarchs, historical figures, and protective deities, such as the compelling and monumental Portrait of Bodhidharma, or the serene, flowing lines of Figure of a Woman.

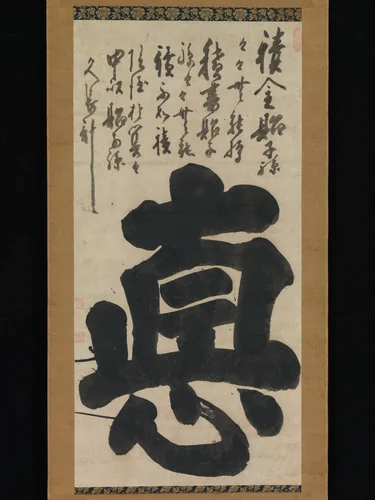

Hakuin was highly adept at depicting compassion in action, as seen in his related compositions, Kannon by a Lotus Pond and Kannon in a Lotus Pond. These Hakuin Ekaku paintings served a crucial didactic purpose, guiding his students and engaging the lay public, an approach that dramatically broadened Zen’s appeal. Works like the terse calligraphic rendering of "Virtue" demonstrate his ability to transform simple characters into powerful, emotive statements.

Although he succeeded in establishing the philosophical framework that continues to define Rinzai practice to the present day, it is a curious historical footnote that Hakuin never formally received dharma transmission from a recognized master. This fact underscores the sheer force of his personal conviction. Today, his singular works are held in premier institutions globally, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Cleveland Museum of Art, ensuring that these museum-quality examples remain central to the study of Edo period art. Fortunately for scholars and enthusiasts, a significant number of his images are available as downloadable artwork, extending his pedagogical influence into the modern era.

Source: Wikipedia · CC BY-SA 4.0