Georgina Cowper

Georgina Elizabeth Cowper-Temple, Baroness Mount Temple (1822-1901), occupies a specific, pivotal space within Victorian history, known widely for her robust philanthropic and moral campaigning. Yet, a focused analysis of her surviving material reveals an early and sophisticated engagement with the nascent art of photography. Active primarily around 1855, her limited, focused oeuvre positions her as a distinctive amateur practitioner whose work documented the intimate social circles of the English aristocracy.

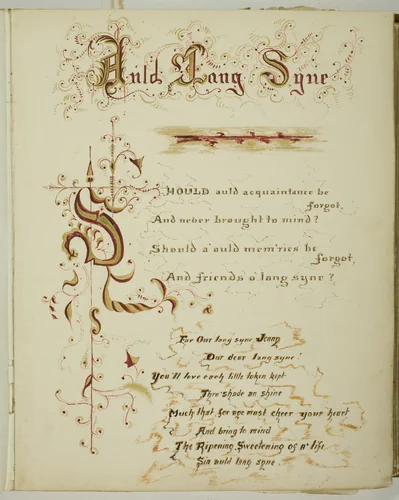

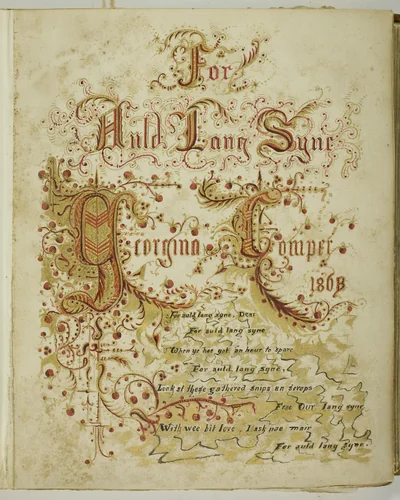

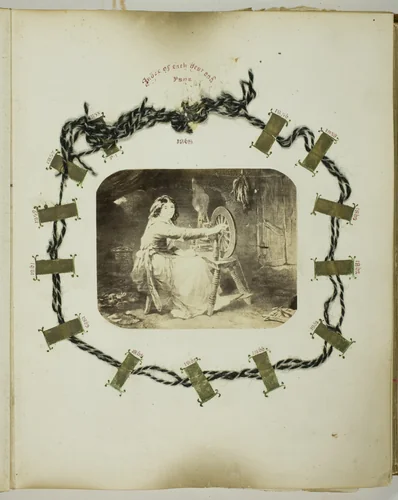

The core of Cowper’s artistic contribution rests within the handful of surviving untitled photographs and the remarkable documented volume known as the Auld Lang Syne Album. This album serves as a crucial visual record of mid-19th century English life, offering candid and immediate glimpses into the private sphere of her husband, William Cowper-Temple, 1st Baron Mount Temple, and their esteemed visitors. Unlike the stilted, formal portraits typical of the decade, Cowper’s images often possess a domestic vitality, highlighting the quiet dedication required to master the cumbersome equipment and chemical processes of the early Victorian photographic studio. The rarity and clarity of these documents have secured their place within major institutional holdings, including the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Beyond the lens, Lady Mount Temple was a formidable figure in social reform. She dedicated significant energy to the Temperance Movement and was a powerful voice for animal welfare, co-founding the influential Plumage League and actively supporting the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA). It is perhaps this duality—the coexistence of exacting moral campaigning and the patient, precise execution demanded by early photography—that makes her visual output so intriguing. She was, simultaneously, a leading figure demanding societal purity and a quiet innovator documenting the reality of her social world.

Her lasting significance rests not only in her humanitarian efforts but also in these rare visual artifacts. As these early photographs transition into broader accessibility, the originals now often residing in the public domain, they provide excellent source material for scholars. These documents are increasingly available as museum-quality prints, securing Georgina Cowper’s place as a minor but vital contributor to Victorian photographic history. Researchers can now readily find downloadable artwork derived from these original photographic studies, granting new access to her precise vision.