George Meek

George Jackson Meek, active primarily across Scotland and later England between 1835 and 1850, is recognized today as a vital specialist in the increasingly refined art of Victorian sentimental ephemera. Meek’s fifteen-year career coincided with the commercialization of romantic correspondence, a transition he profoundly shaped by elevating the handmade valentine from folk craft to intricate, layered artistic output. His works are collected by institutions globally, notably featuring in the permanent holdings of the Art Institute of Chicago.

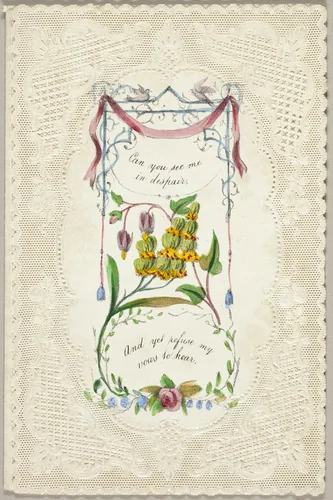

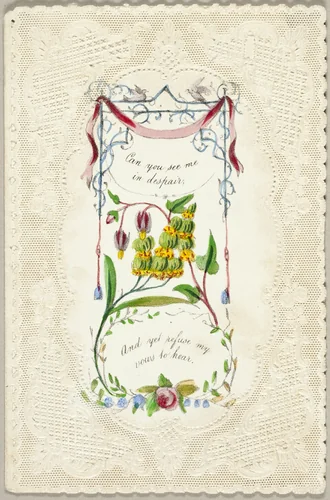

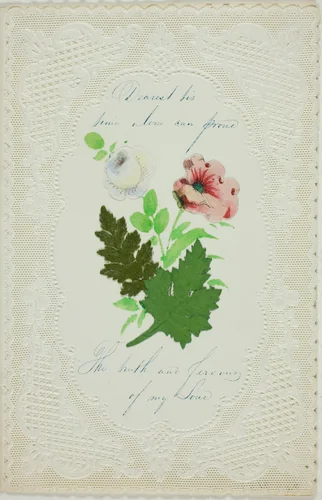

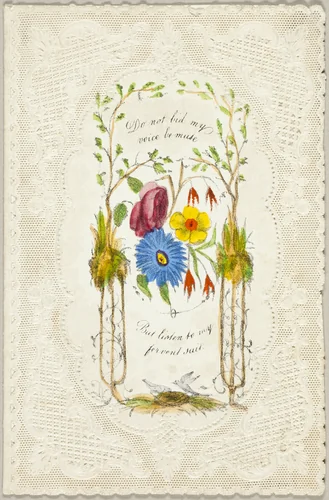

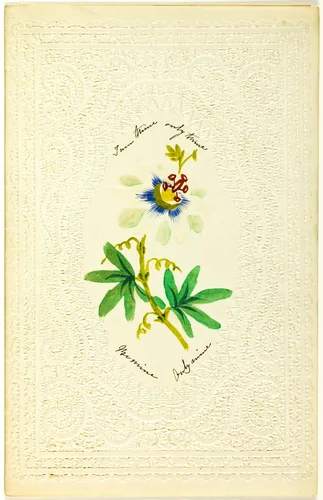

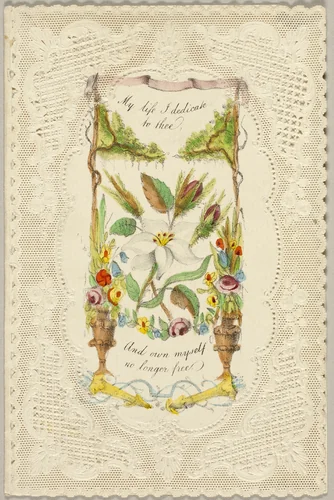

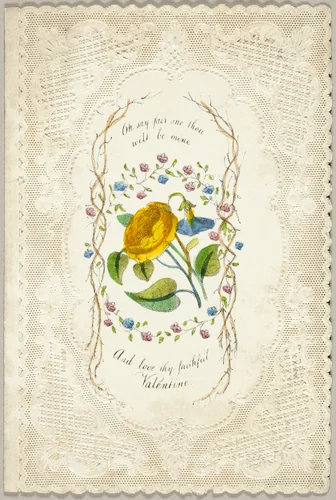

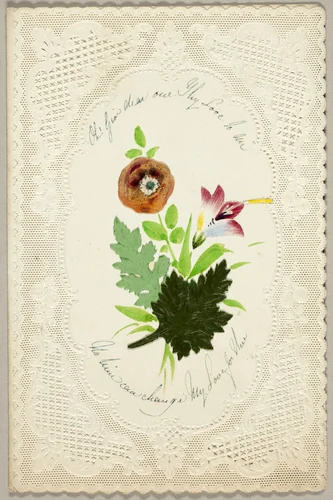

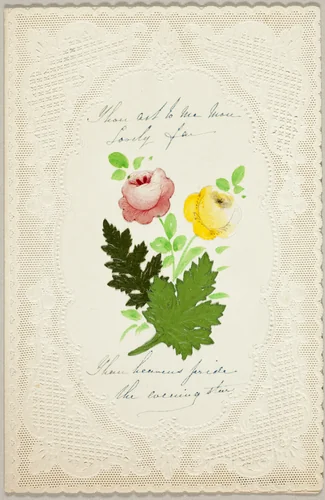

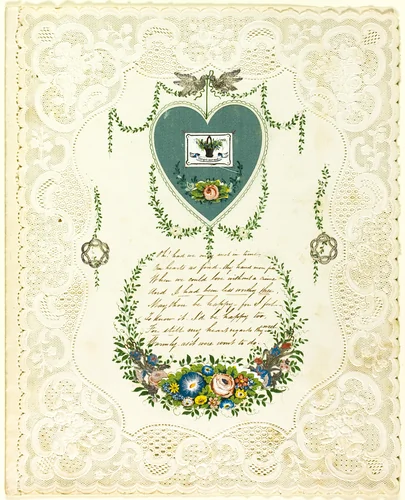

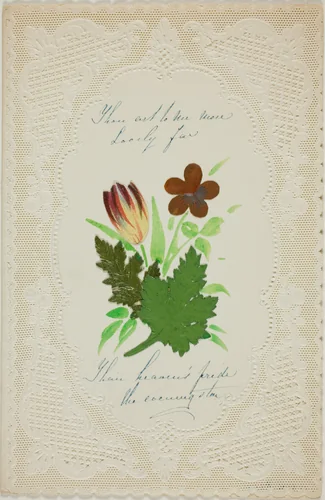

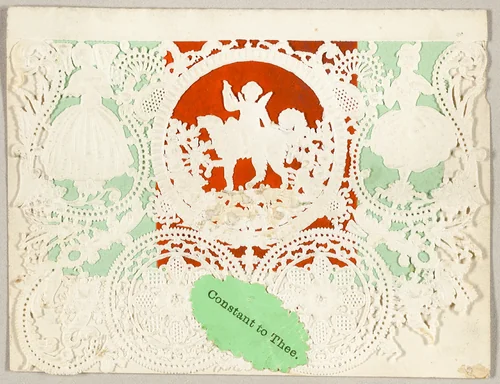

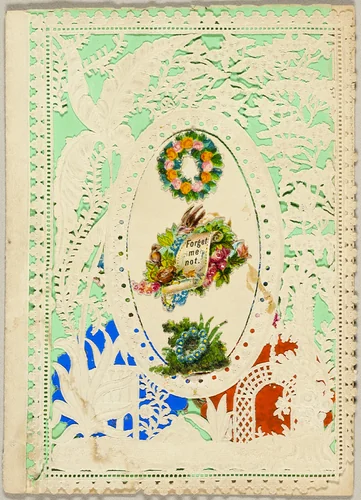

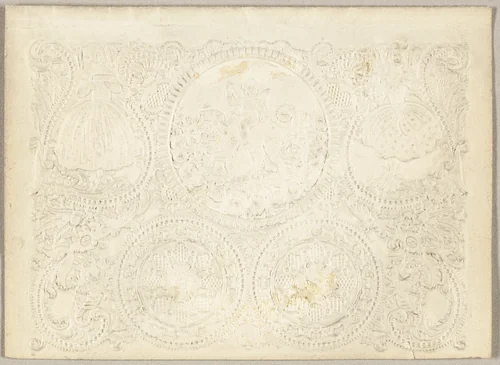

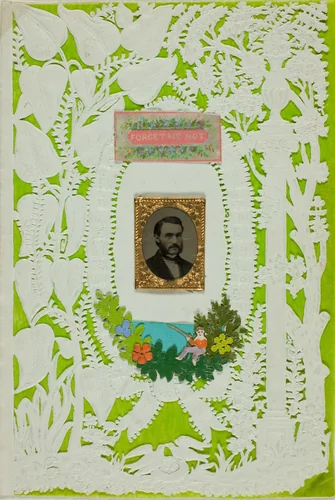

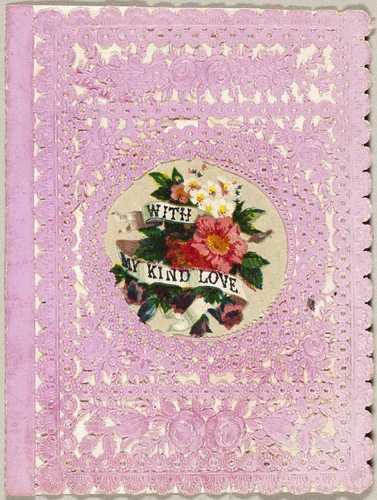

Meek's lasting significance rests on his technical mastery of the paper medium. Moving beyond simple verse and traditional woodcut illustration, he utilized complex folded constructions, delicate die-cut lace paper, and coded floral imagery. He was instrumental in popularizing the use of three-dimensional fleurs d’amour embedded within the composition, providing the recipient with not only a message but a sophisticated, miniature sculpture. These meticulously constructed objects served as intense, coded communications within the stringent social framework of the early Victorian era.

While the inherent anonymity of the genre obscures the precise number of surviving compositions, it is estimated that Meek’s studio designs influenced nearly 400 contemporary pieces, setting a new, exacting benchmark for the burgeoning mass-market greeting card industry. Meek’s attributed works, such as Can You See Me in Despair? and Dearest 'Tis Time Alone, illustrate his penchant for conveying urgent, almost melodramatic sincerity. Approximately fifty major designs or prototypes are confidently assigned to his hand, indicating a period of high productivity focused exclusively on this highly demanding form of material culture.

The enduring interest in Meek’s work stems not only from their historical representation of early communication rituals but their sheer beauty. These delicate originals are difficult to preserve, yet through modern digitization, many of his elegant designs are entering the public domain, allowing curators and enthusiasts access to high-quality prints and downloadable artwork. The singular, understated observation regarding Meek’s legacy is that this master of personal, secret correspondence, whose entire output centered on articulating profound intimacy, remains historically known almost exclusively through the sheer volume and quality of his anonymous paper output.