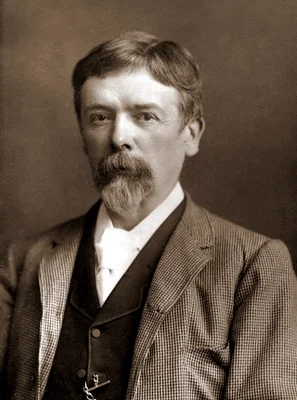

George Du Maurier

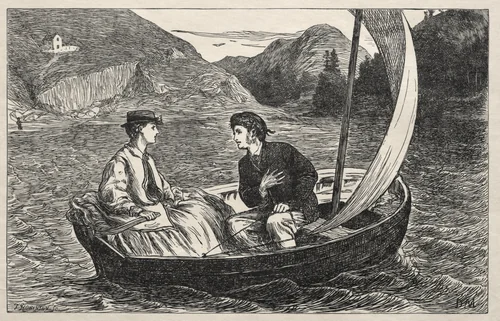

George Louis Palmella Busson du Maurier (1834-1896) occupies a significant place in the narrative of late Victorian visual culture, balancing careers as an illustrator, cartoonist, and novelist. A French-British artist, Du Maurier’s primary vehicle for disseminating his sophisticated visual commentary was the satirical magazine Punch, where his detailed, often observational illustrations became a defining feature of the publication throughout the latter half of the nineteenth century. His work is held in prestigious international collections, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Cleveland Museum of Art, testament to his enduring influence on graphic art.

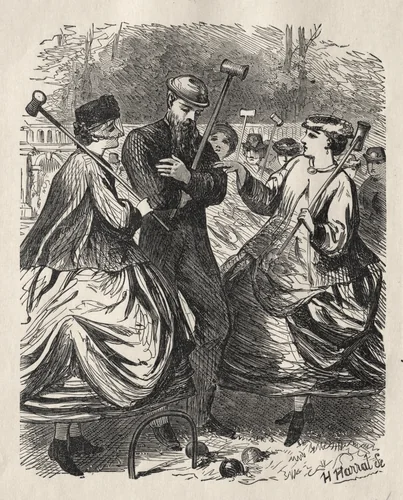

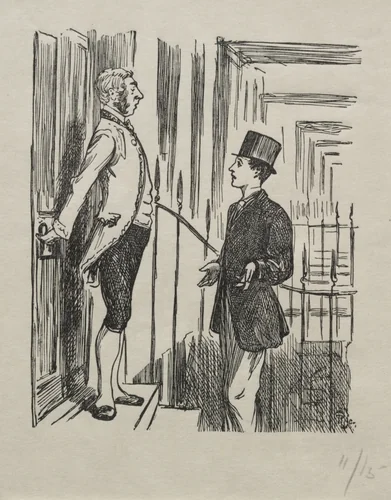

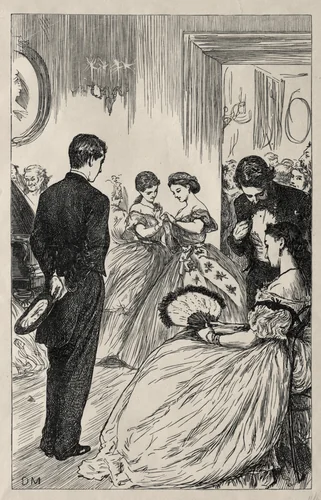

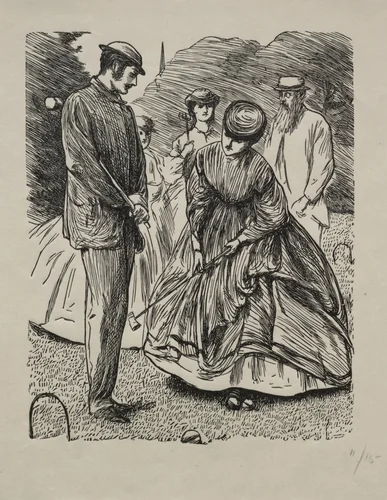

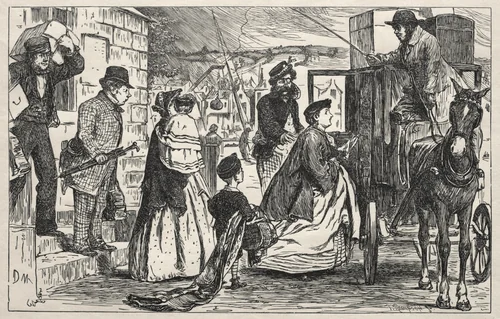

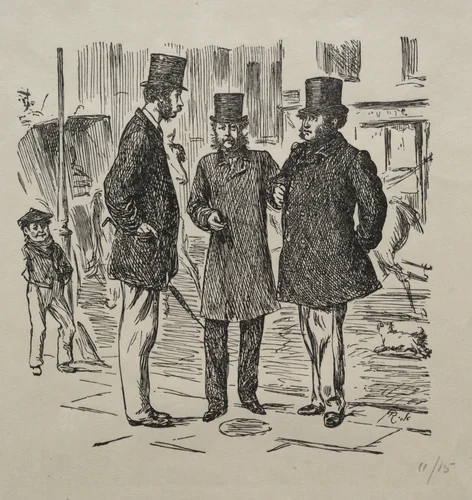

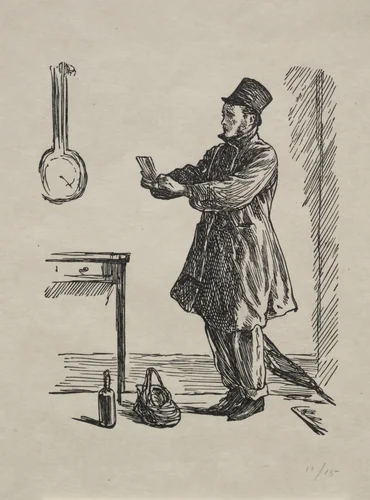

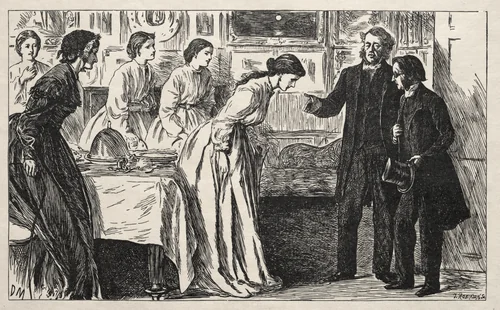

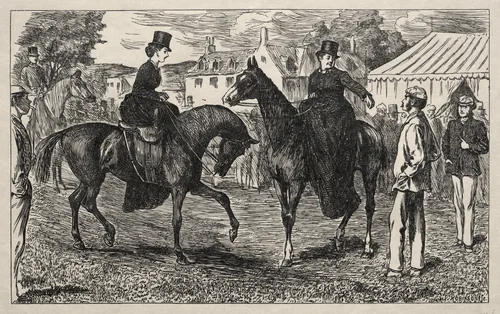

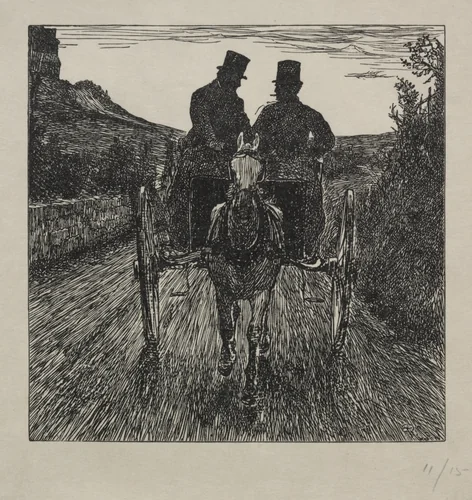

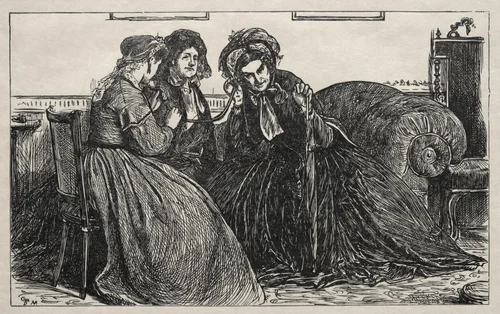

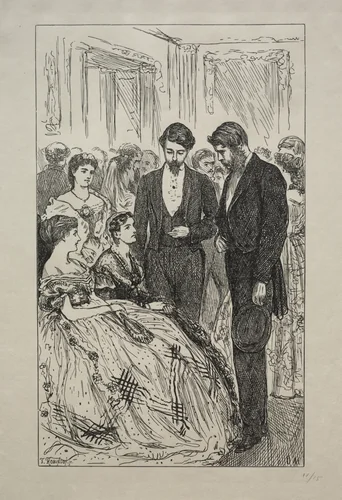

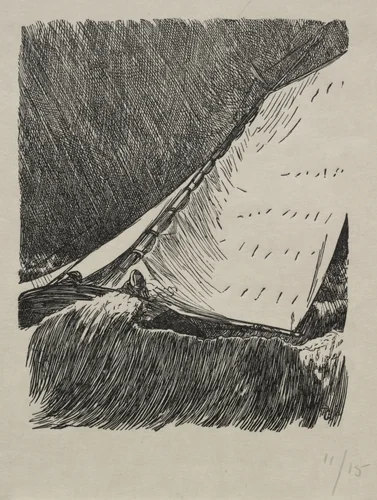

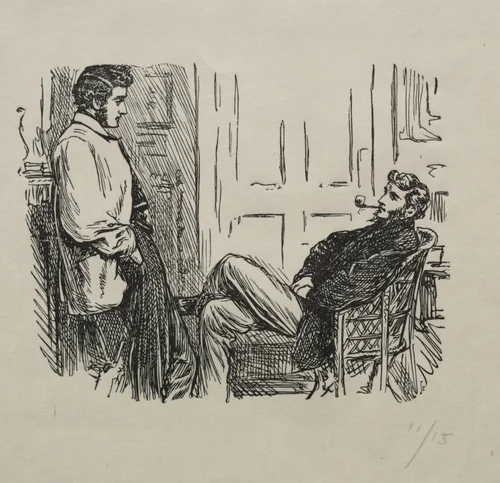

Du Maurier’s technical skill is best demonstrated through the extensive catalogue of drawings and prints he executed during his most active artistic period. He frequently engaged in exacting studies from life, transforming subjects that might seem incidental, such as the focused observation in Gecko: study from life or the dynamic capture of motion in Conductor: study from life and Violinist: study from life, into compelling, stand-alone works of art. This dedication to detailed realism elevated the quality of his professional illustrations. Du Maurier was a particularly astute and witty observer of social stratification, often employing a light, knowing sarcasm toward the pretensions and anxieties of the rising middle and upper classes, a trait that makes his visual humor still remarkably relevant.

While his fame as an illustrator was considerable, Du Maurier achieved lasting cultural omnipresence through his literary output. His 1894 Gothic novel, Trilby, introduced the mesmerizing and manipulative character Svengali, whose name immediately entered the English lexicon to denote controlling influence. This crossover illustrates Du Maurier’s unique capacity to shape popular imagination through both visual and written means.

The foundation of his literary work, however, remains rooted in his visual practice. Today, scholars and enthusiasts appreciate the range of his original output. Due to the era in which he worked, many of his finest creations, including prints like "The Woman That Was", are now in the public domain, making high-quality prints and original sketches accessible as downloadable artwork for academic study and personal appreciation.

Source: Wikipedia · CC BY-SA 4.0