George Catlin

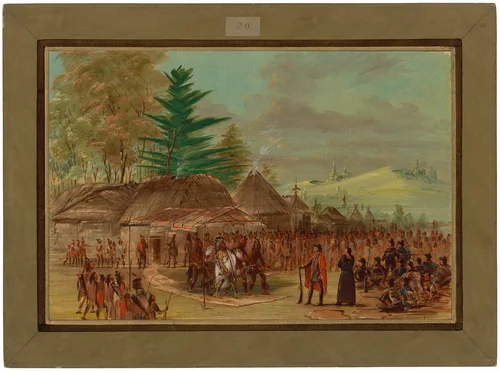

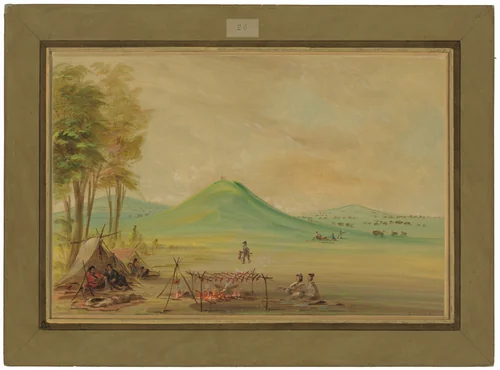

George Catlin (1796-1872) holds a foundational position in the history of American documentary art, having abandoned a legal career to devote his life to creating an unprecedented visual record of Native Americans living on the Western frontier. Recognizing the imminent threat posed by westward expansion, Catlin dedicated himself to capturing the cultures of the Plains Indians, motivated by an urgent sense of historical preservation.

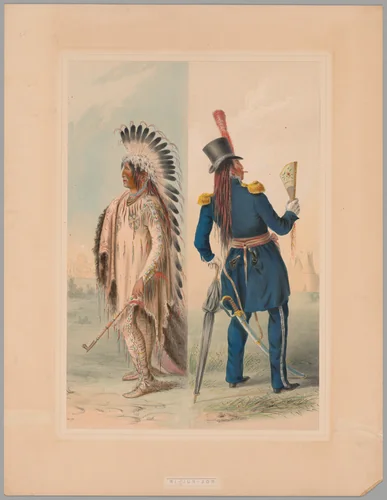

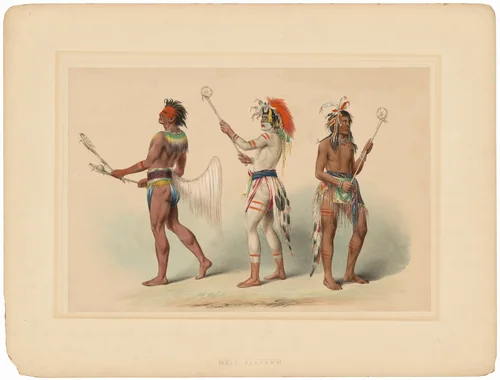

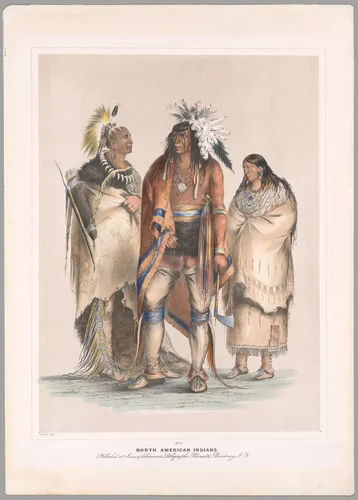

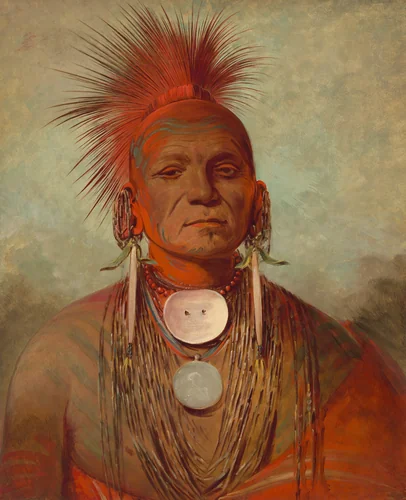

Between 1830 and 1839, Catlin undertook five extensive journeys into the American West. Serving simultaneously as a painter, traveler, and author, his methodology was systematic, resulting in an extraordinary collection of portraits and scenes depicting daily life and custom. These George Catlin paintings provided the Eastern public with their first detailed understanding of these societies. His portraits often carry an ethnographic weight, capturing both individual likeness and cultural context, evidenced in works such as The Female Eagle - Shawano and the culturally significant two-part observation, Wi-Jun-Jon - The Pigeon's Egg Head Going to Washington: Returning to his Home.

Catlin’s commitment to visual communication was established early in his career through technological innovation. Before his expeditions west, his work included producing precise engravings, drawn from nature, detailing sites along the route of the Erie Canal in New York State. Several of these renderings, featuring early images of the city of Buffalo, were notably published in Cadwallader D. Colden's Memoir (1825), recognized as one of the first American books to utilize lithography.

While his initial success rested on publishing innovations, Catlin’s lasting legacy is rooted in his monumental project of ethnographic portraiture. His works, including Mrs. George Catlin (Clara Bartlet Gregory) and Boy Chief - Ojibbeway, are today considered essential historical artifacts. Major museums, including the Art Institute of Chicago and the National Gallery of Art, house significant collections of Catlin’s output. Consequently, much of his visual archive is now in the public domain, making high-quality prints and downloadable artwork accessible for scholarship and appreciation worldwide. His comprehensive documentation remains a vital, if sometimes complex, resource for understanding nineteenth-century American history.

Source: Wikipedia · CC BY-SA 4.0