Gabriel Huquier

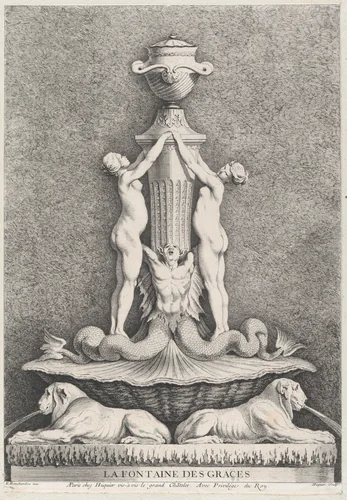

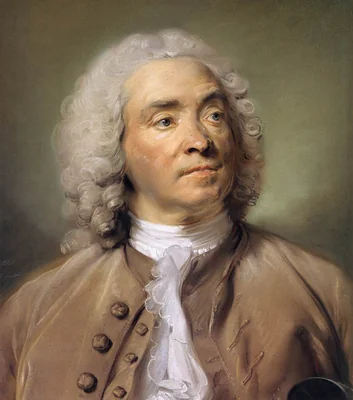

Gabriel Huquier (1695–1772) was a central figure in the proliferation of 18th-century French visual culture, operating primarily as a drawer, engraver, and publisher. His significance rests not merely on individual artistic output, but on his critical entrepreneurial role in making ornamental design accessible throughout Europe. Huquier served as a vital nexus between the conceptualization of Rococo aesthetics and their mass commercial realization, shaping contemporary taste during the transition from the late Régence into the mature Louis XV period.

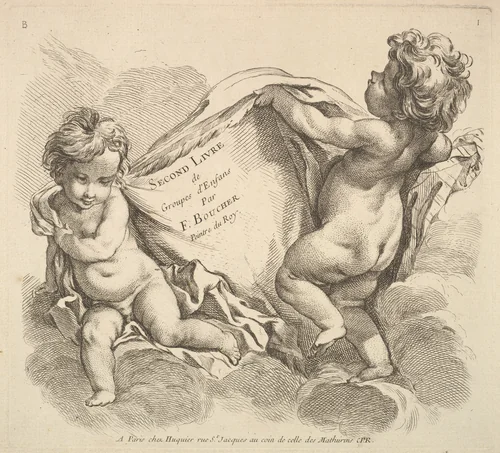

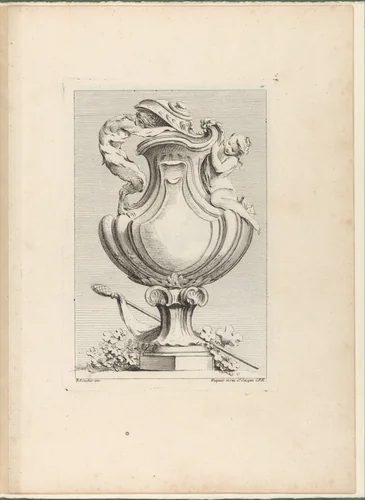

Unlike artists focused solely on painting or sculpture, Huquier mastered the complex commercial apparatus of printmaking. He functioned as both artisan and editor, commissioning works and ensuring their rapid circulation to designers, architects, and private patrons seeking the latest Parisian fashions. His catalogue, which included at least two known published books and numerous individual print series, established the decorative standard for interior architecture, furniture, and especially the fashionable import of chinoiserie, exemplified by intricate works such as A Chinese Man and Woman Fishing by a Fishpond.

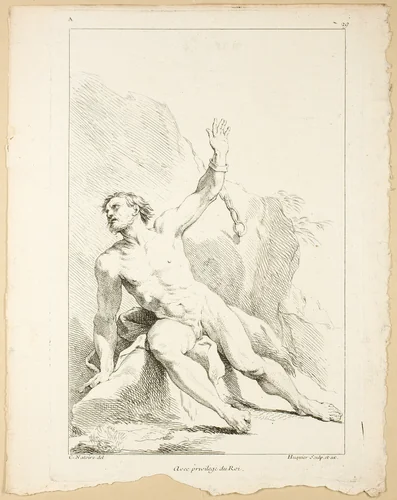

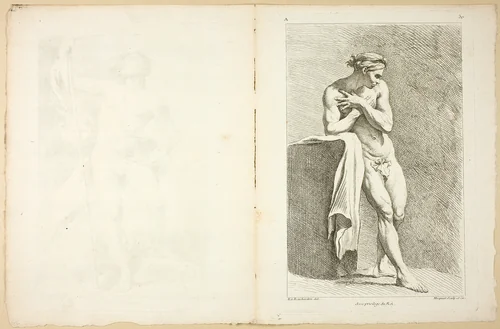

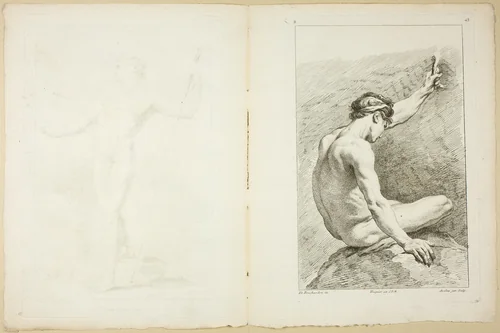

The technical precision demanded by his business is evident in his remaining body of work. Engravings such as Faith and Charity showcase the detailed rendering required for museum-quality imagery. Conversely, his capacity for satire is highlighted in the series featuring the unfortunate, frequently nude, Ragotin, whose comical misadventures are documented in prints like Ragotin valt van de wagen. Huquier was known for his vast collection of prints and drawings, utilizing them not merely for personal pleasure but as immediate source material for new publications, establishing a highly efficient commercial feedback loop. It is a subtle irony that an artist so concerned with commercial exclusivity now sees many of his influential Gabriel Huquier prints widely available in the public domain.

Huquier’s contribution transcended mere artistry; he defined the mechanisms by which art and decoration were consumed in the Enlightenment era. His dedication to the graphic medium allowed for the broad, systematic distribution of complex ornamental schemas, cementing the visual vocabulary of the French Rococo throughout the continent. Today, his surviving output is preserved in elite institutions such as the Art Institute of Chicago, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Rijksmuseum, validating the enduring influence of these high-quality prints on the history of design.

Source: Wikipedia · CC BY-SA 4.0