Furuyama Moromasa

Furuyama Moromasa was a highly competent Japanese Ukiyo-e painter and print artist whose active period spanned the first half of the eighteenth century, operating approximately between 1707 and 1740. His documented output marks a transitional moment in the development of the ukiyo-e genre, bridging the earlier, more stylized narrative traditions with the emerging focus on specific, individualized beauty and detailed theatrical portraiture. Moromasa worked successfully across multiple formats, establishing his command of both complex genre scenes and individual figure studies.

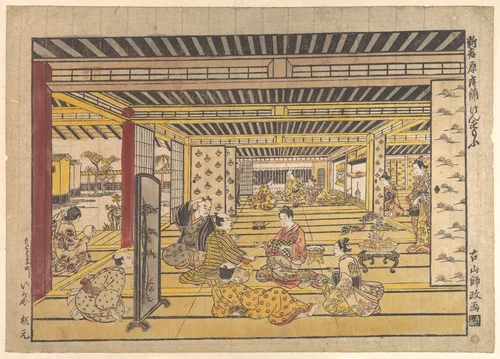

His artistic versatility is evident in the surviving corpus, which includes preparatory works, key prints, and significant Furuyama Moromasa paintings. Whether executing large, dynamic public scenes such as the panoramic Gathering Shellfish at Low Tide at Shinagawa (Shinagawa shiohigari no zu) or capturing intimate, focused moments like Courtesan Resting on the Veranda, Moromasa demonstrates a keen ability to manage complex compositions while conveying atmospheric detail. His theatrical work, exemplified by the striking Portrait of Ichikawa Danjuro II as Kamakura no Gongorô, solidifies his critical role in popularizing and formalizing early Kabuki iconography for mass distribution.

Moromasa’s interest often gravitated toward the fleeting pleasures of the Yoshiwara district and the bustling activities of the common populace. Scenes like A Game of Hand Sumo in the New Yoshiwara offer a spirited, unvarnished look at social customs, reminding the viewer that high-stakes theatricality sometimes took place outside the theater walls. The artist’s capacity to depict both the grand mythological, as seen in the auspicious design of The Treasure Ship, and the everyday spectacle confirms his status as a perceptive and highly skilled chronicler of the ‘floating world.’

Although his overall active period was limited, Moromasa’s enduring reputation is secured by the consistent quality of his output and his inclusion in major global institutions, including the Art Institute of Chicago and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. For scholars and enthusiasts today, his artistic output is increasingly accessible; many of his finest compositions are held in the public domain and available as downloadable artwork. These museum-quality high-quality prints continue to provide essential insight into the technical and thematic development of early eighteenth-century Japanese genre representation.

Source: Wikipedia · CC BY-SA 4.0