Elizabeth Johnson

Elizabeth Johnson holds a significant, though specialized, position within the history of American public arts, primarily due to her intensive contributions to the Index of American Design (IAD). Operating under the auspices of the Works Progress Administration (WPA), the IAD initiative, active primarily from 1935 to 1942, sought to create a comprehensive “visual encyclopedia” of historical American material culture. Johnson’s rigorous output during this period helped define the project’s high standards for technical illustration and documentation.

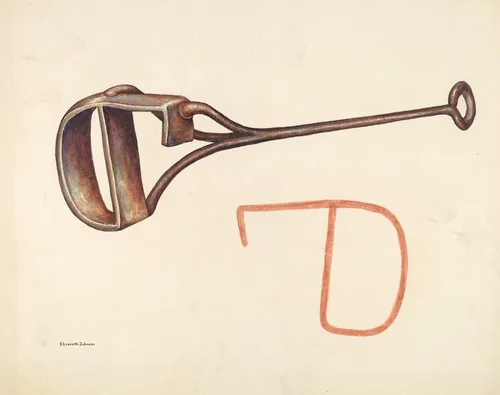

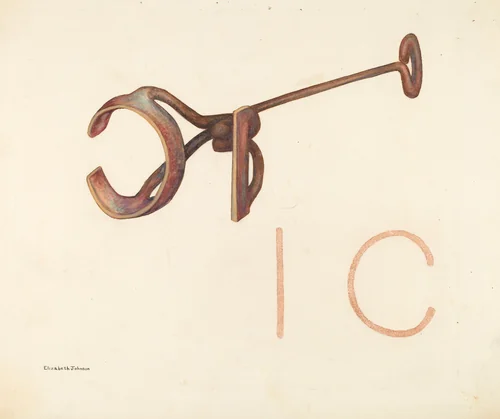

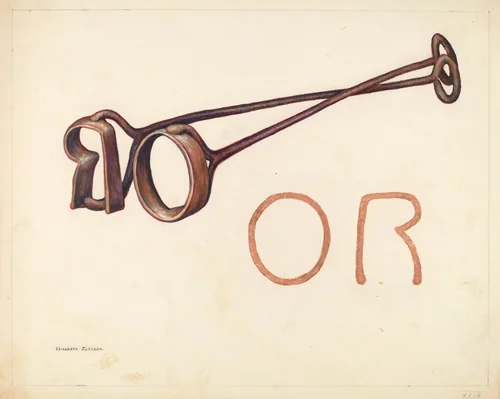

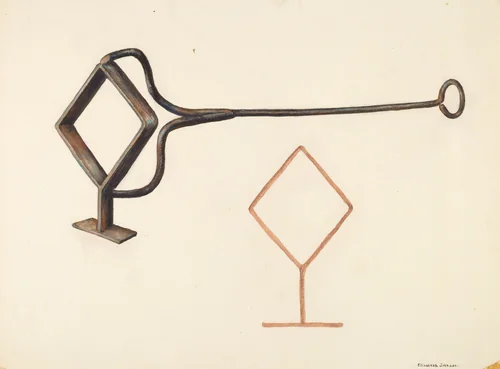

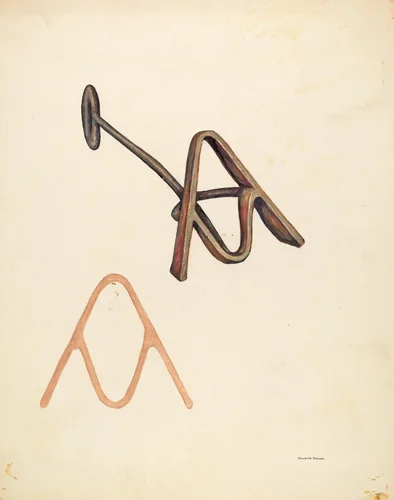

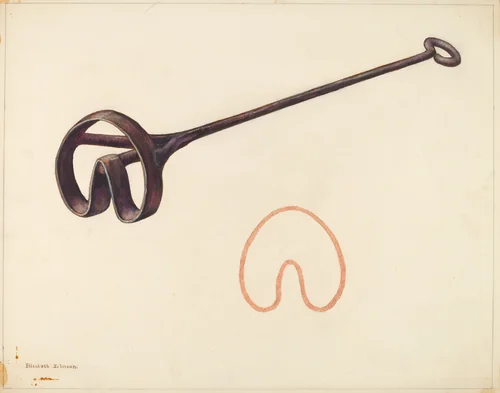

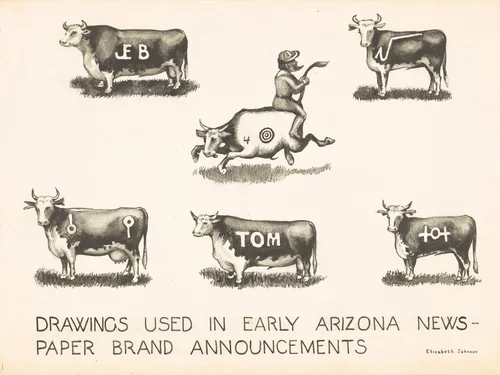

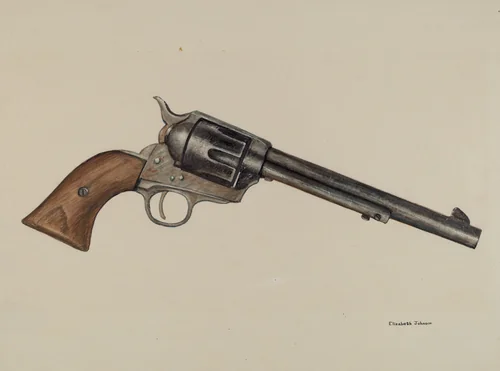

The IAD required participating artists to function as precise recorders, translating three-dimensional artifacts into two-dimensional studies suitable for future educational use. Johnson excelled in rendering artifacts related to early industrial and frontier life, capturing objects that spanned both folk art tradition and practical necessity. Her catalog is characterized by a dedication to utilitarian forms, particularly evident in the fifteen known entries she contributed to the Index.

Johnson’s focused documentation, often utilizing a combination of watercolor and gouache, elevates the mundane to the status of studied historical record. The repeated appearance of the Branding Iron in her known body of work, meticulously documented in multiple views to show scale, material, and fabrication methods, demonstrates a commitment to rendering these tools of the American West with exacting fidelity. Unlike traditional fine art practices focused on expression, her work prioritized conservation through meticulous visual description, generating invaluable visual data for future generations.

The successful preservation of the IAD archive ensures Johnson's legacy remains tangible. Today, the entire collection is housed at the National Gallery of Art, where her original documentation is maintained as museum-quality cultural property. Reflecting the WPA's original goal of widespread education, her detailed drawings and Elizabeth Johnson prints are frequently found in the public domain, offering historians and designers valuable, royalty-free insight into America's functional past. It is an interesting note of historical anonymity that an artist whose precision gave such clarity to inanimate objects is herself defined mostly by the commonality of her name, underscoring the powerful, yet collective, nature of this crucial Depression-era project.