Cornelis Drebbel

Cornelis Drebbel (c. 1572–1633) stands as one of the Dutch Golden Age’s quintessential polymaths, a figure whose career trajectory charts the transition from classical artistic representation to modern scientific engineering. While Drebbel is globally recognized as an influential inventor, responsible for crucial developments in optics, chemistry, and control systems, his earliest recorded professional output was as a prolific printmaker active between 1587 and 1596.

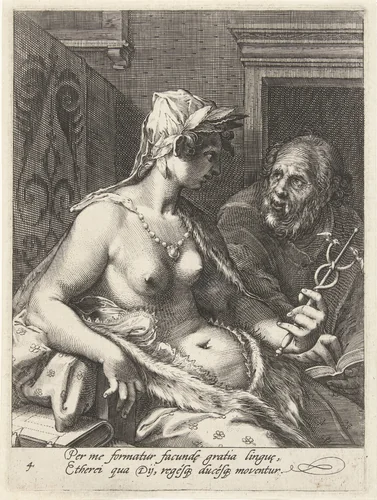

This initial artistic period demonstrates an intellectual rigor that would define his later scientific achievements. Drebbel’s prints were not focused on portraiture or landscape, but on the systematic categorization of knowledge, reflecting the intense philosophical inquiry of the late 16th century. His surviving works, held in distinguished collections including the Rijksmuseum and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, include a conceptual suite illustrating the core elements of liberal arts, such as Logica, Muziek (Musica), Rekenkunde (Aritmetica), and Retorica. Similarly, the print Touch formed part of a sequence exploring the Five Senses. These Cornelis Drebbel prints operate as visual schematics, utilizing detailed engraving to give form to abstract intellectual disciplines.

This foundational commitment to structure and precision provided the template for his engineering innovations. Drebbel soon moved from the symbolic organization of knowledge to the physical manipulation of reality. He became a pioneering figure in instrument design, notably contributing to the development of the thermometer and early closed-loop control systems. Yet, his most audacious achievement remains the construction of the world’s first functioning, steerable submarine, tested in the Thames around 1620. This shift from creating high-quality prints illustrating philosophy to building functional vessels demonstrates a rare capacity for both visual and mechanical synthesis.

Drebbel’s legacy rests on this unique dual mastery. The meticulous detail required for his early artistic output informed the precise engineering necessary for his later inventions. Today, several of these historically significant works reside in the public domain, allowing access to royalty-free images that reveal the early intellectual foundations of a man who ultimately conquered both printmaking and underwater navigation.

Source: Wikipedia · CC BY-SA 4.0