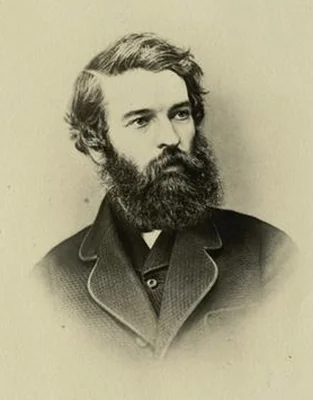

Christopher Pearse Cranch

Christopher Pearse Cranch (1813-1892) holds a unique and historically vital position in 19th-century American visual culture, operating precisely at the intersection of high philosophy and artistic representation. While active primarily as a writer and poet, Cranch’s brief but consequential artistic period between 1830 and 1852 generated foundational images that conceptually defined the nation’s dominant intellectual movement, Transcendentalism.

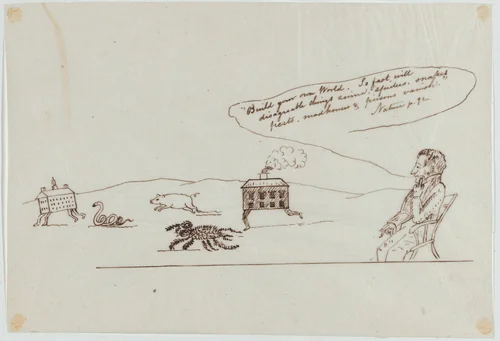

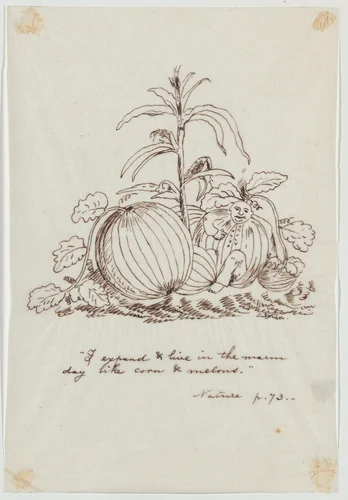

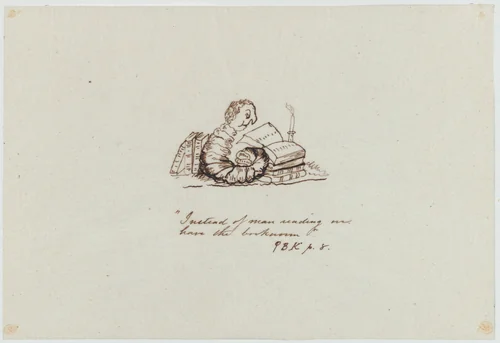

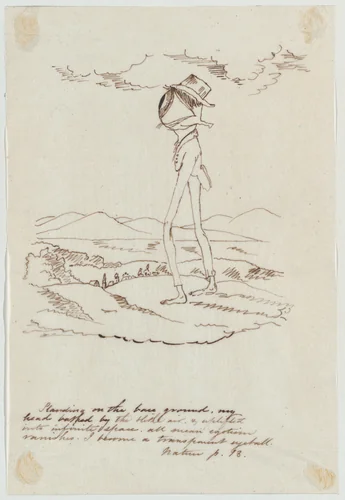

Cranch’s singular contribution lies in his determined effort to translate the sometimes-impenetrable abstractions of Ralph Waldo Emerson’s essay Nature (1836) into accessible visual metaphors. His conceptual drawings, most notably Standing on the Base Ground... I Become a Transparent Eyeball and Build Your Own World. So Fast Will Disagreeable Things...Vanish, are not simple marginalia; they function as philosophical diagrams, attempting to materialize Emerson’s challenging concepts of radical subjectivity and the divine connection inherent in the natural world. This practice, merging rigorous intellectual inquiry with graphic satire and nascent abstraction, marked a truly innovative moment in American illustration. Another characteristic example of his wit and observational skill is the drawing Instead of Man Reading We Have the Bookworm, demonstrating his versatility beyond the purely philosophical.

Cranch’s engagement was not limited to conceptual sketches. He was also affiliated with the aesthetics of the Hudson River School, demonstrating his capacity for traditional landscape interpretation. His painting Castle Gondolfo, Lake Albano, Italy illustrates his command of the picturesque tradition, a common endeavor for American artists studying abroad. It is perhaps slightly ironic that the man who visually interpreted the quintessential American call to self-reliance spent significant periods of his career traveling through Europe, contributing to a rich body of Christopher Pearse Cranch paintings and drawings informed by both Old World and New World aesthetics.

Despite the relatively short duration of his serious visual art production, Cranch’s work maintains significant museum-quality institutional relevance. His drawings, alongside his single known painting, are held in major public repositories, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the National Gallery of Art. For scholars tracing the genesis of American philosophical art, these pieces remain central documents. Today, Cranch’s drawings frequently reside in the public domain, ensuring their continued accessibility as sources for high-quality prints and scholarship worldwide.

Source: Wikipedia · CC BY-SA 4.0