Bonaventura van Overbeek

Bonaventura van Overbeek (1660–1705) stands as a foundational figure among the Dutch Golden Age draughtsmen who specialized in chronicling the vanishing glories of classical Rome. Though his life was cut short, his impact resonates through a precise and authoritative body of engraved work, active around 1708, which cemented the visual understanding of antiquity for subsequent generations of artists, architects, and scholars.

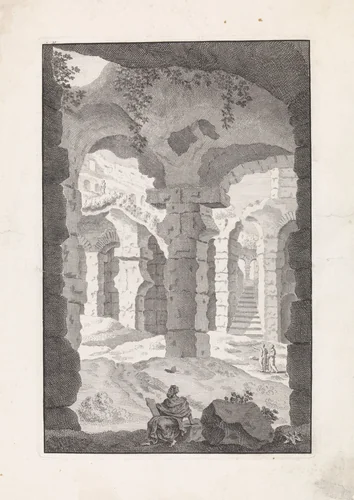

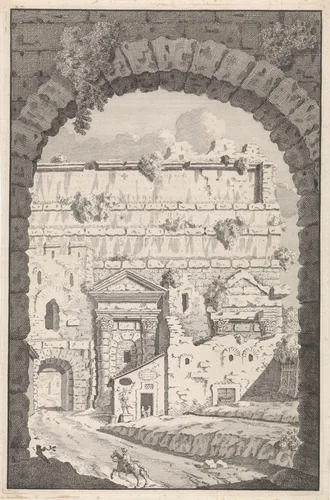

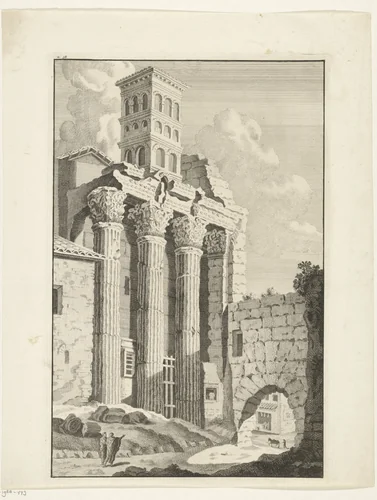

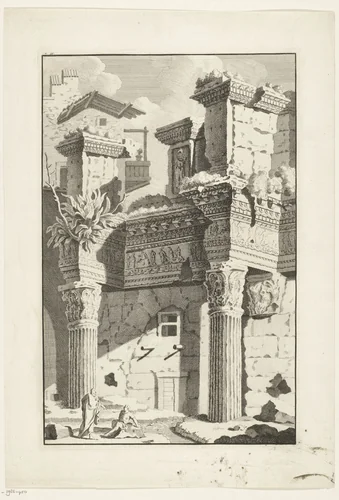

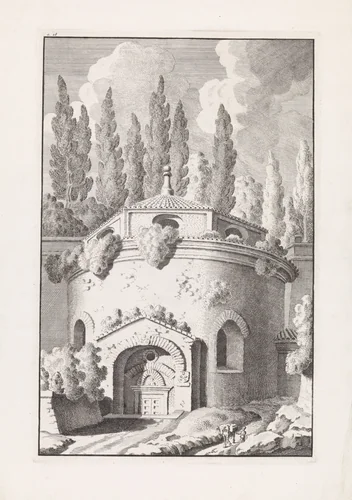

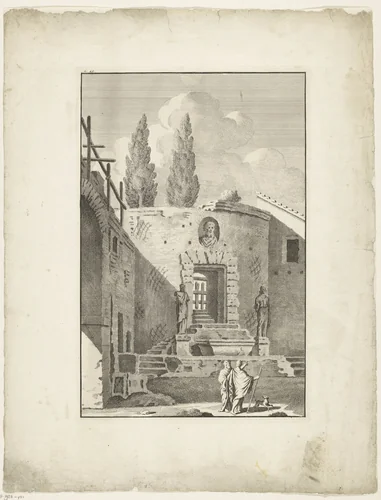

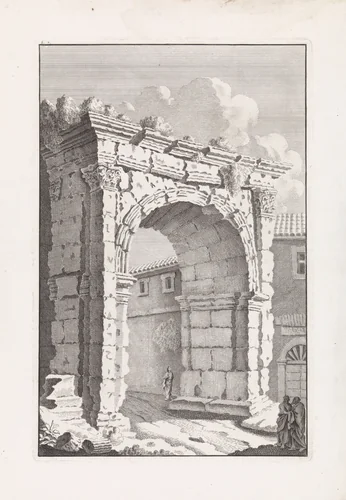

Overbeek’s significance derives from his commitment to documenting the Eternal City’s structures when they were often overgrown or rapidly deteriorating. Unlike earlier artists who might romanticize or simply utilize ruins as atmospheric background elements, Overbeek approached them with an almost archaeological rigor. His engravings functioned less as scenic views and more as structural case studies. Works such as Romeinse ruïne met drie korinthische zuilen and Gezicht door een boog op een ruiter en ruïnes showcase his ability to render complex architectural compositions, demonstrating both the massive scale and the delicate decay inherent in classical structures.

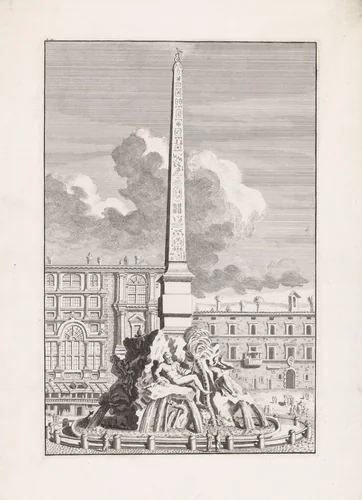

The meticulous detail required of an engraver specializing in these complex subjects demanded a high level of technical mastery. The precision of his line work transformed what might have been merely historical records into powerful artistic statements. He was particularly successful in capturing the juxtaposition of the ancient world with contemporary life, as seen in pieces like Agonalis obelisk met de Fontana dei quattro fiumi, where the colossal monuments are integrated seamlessly with the functioning Baroque urban fabric. One might observe that for a man primarily focused on the vestiges of the past, Overbeek proved remarkably adept at capturing the ephemeral present.

While few Bonaventura van Overbeek paintings exist-his primary output focused on preparatory drawings and subsequent prints-his legacy rests on his successful translation of three-dimensional observation into reproducible media. This was critical in the early eighteenth century, allowing his studies to circulate widely across Europe. The resulting high-quality prints ensured that his vision of the classical world endured far longer than the artist himself. Today, these crucial visual documents are housed in leading institutional collections, including the Rijksmuseum, and are often available for educational purposes as many of these important architectural records now reside in the public domain.

Source: Wikipedia · CC BY-SA 4.0